Marketplace

2018 Matador Records PRESSING

- Catalog Number OLE-1146-8

- Release Year 2018

- Pressing Weight Regular Weight

- # of Disks 2

- Vinyl Color Baby Blue

- Jacket Style Gatefold

When listening to this album I think of this band or music:

All Kurt Vile records—and Bottle It In is no different—tend to feel relatively familiar. And yet each one of his works remains somewhat elusive, with direct references hard to pinpoint. The Philadelphia-based artist, now nearing 40 and by all accounts a relatively normal and well-adjusted family man, creates music that feels woozy—fare that once, perhaps, existed as beautifully concocted folk-rock but somehow got lost. The songs are melodic, but instead of giving the listener something to which to sing along, they launch into orbit.

Vile’s approach is not quite psychedelic but not exactly Americana, either. His material possesses hints of Neil Young at his most cosmic, Willie Nelson at his most stoner, and Tom Petty at his most introspective. As should be evident by Vile’s association with Matador Records, he’s also steeped in indie rock. The slacker tone of Pavement is present, as is the calming nature of Cat Power. The easiest way to think of Vile: He exists somewhere between Will Oldham and Bruce Springsteen, and wouldn’t sound out of place on a bill with either artist.

Music from this album would be a great soundtrack to this movie:

If Vile’s music is not quite mainstream, it’s mainstream adjacent. Maybe it owes to the way the songs drift, or the way in which Vile’s intricate guitar goes for a groove rather than a riff. By extension, one cinematic character who would no doubt be very into Vile’s music is the Dude. The Coen brothers’ creation, brought to life by Jeff Bridges in The Big Lebowski, has a devil-may-care attitude—one that remains borderline hippie but also laced with an edge—in the way he goes through life. After all, the Dude hates the Eagles, and the slick romanticism of that California band seems the opposite of all-things Vile. The latter’s songs tumble and ramble and seemingly reveal great truths or life lessons, but may also be a joke. “Don’t tell them that you love them,” Vile sings in the title track, before adding at the end of the couplet, “’Cause you never know when your heart’s gonna break.”

Bottle In In is no hurry whatsoever to get to wherever it’s trying to go.

The record’s 80-minute run time, coupled with Kurt Vile’s relaxed vibe, rewards those seeking simple pleasures rather than immediacy. Even when the guitars start to flex a bit of muscle—see the Western tones and digital rhythms of “Check Baby”—this is still rock n’ roll that could have easily been performed in a wooden rocking chair while basking in the comfort of a back porch. Bottle It In shifts tempos and peppers songs with about the same amount of details as Vile’s other recent works, begetting the sonic sensation of feeling dazed.

As a songwriter, Vile remains his sharpest when he’s direct, although even then, Vile is prone to diversions and random thoughts. Call it ADD at it most chill, but it’s still worth taking Vile’s tour of Philly on “Loading Zones,” essentially a song about doing errands. But the sophisticated albeit up-tempo guitar work, as well as the chanting in which Vile’s backing band brags about parking for free, gets to the core of the record’s everyday charms.

Ditto the languid “Hysteria” and “Yeah Bones,” the former an ode to long-term commitment in which Vile compares love to rabies and the latter caked with twisty guitar knots to calm one’s nerves (relax, and put down the smartphone, people). Bits of weirdness creep into “Bassackwards,” where a harp sounds controlled by a knob and Vile offers what serves as a mission statement for his whole catalog: “I was chilling out, but with a very drifting mind.” He isn’t kidding, for when the banjo of “Come Again” appears to signal Vile prepared to spin an outlaw tale, he stops paying attention and loses his train of thought.

“Come again, come again,” he sings, “What was that you said?” It doesn’t matter. Vile’s songs reside somewhere between a daydream and an REM sleep cycle.

While not clearly marked on the packaging, our retail-purchased review LP set is the regular-weight, soft baby-blue-colored vinyl edition. The quality of the pressing boils down to a tale of two LPs, with the first slab strikingly flat and astonishingly quiet. The second LP? Not so much. It has some visible warp, and a bit of noise here and there—primarily noticeable for not matching the high bar set by the first LP. The sound isn’t especially warm, and a haziness keeps the listener at a slight distance. A modest boost in instrumental tone and texture would be welcome. Yet the artwork on the gatefold jacket and the inclusion of accompanying paper inner sleeves add some flair. The cardboard housing is thin but reflects a vintage design that mirrors that of a K-Tel compilation from the 70s. It even features faux ring wear to make it look used. Pretty cool.

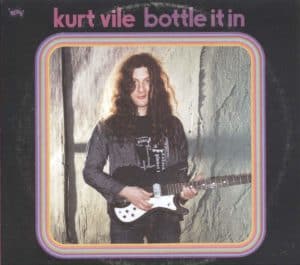

Bottle It In

3.5

3.5