The Clash, for all intents and purposes, ended in 1983, shortly after the release of Combat Rock. The album spawned two of the band’s biggest hits in the U.S., “Should I Stay or Should I Go” and “Rock the Casbah,” which meant the group fizzled out at the height of its popularity.

Yet the final chapter ultimately wasn’t written until 2002, the year co-leader Joe Strummer died of a previously undetected congenital heart defect. At the time, he was working on new music. Some of it, former Clash mate Mick Jones later revealed, Strummer hoped could potentially surface on a Clash reunion album.

While new Clash music was always a longshot and is no longer a possibility, today, the singer’s cultural reach remains as vast as ever. Last winter, amid a divisive political and social climate, punk rock veteran turned author and lecturer Henry Rollins invoked Strummer’s name when he said,

“This is not a time to be dismayed, this is punk rock time. This is what Joe Strummer trained you for.”

But it’s not just musicians singing Strummer’s praises.

Earlier this year, Strummer’s words even popped up in a political debate. Beto O’Rourke, the Texas Democratic Senate candidate running against incumbent Ted Cruz, slammed his competitor by stating, “He’s working for the clampdown,” a reference to a song on the Clash’s London Calling in which Strummer used the phrase “working for the clampdown” as a metaphor for the establishment.

Like plenty of leftist artists before him, be it Woody Guthrie, John Lennon, or Bob Marley, Strummer remains a go-to source for those looking for politically minded motivation. It’s no wonder that artists who view music as a force for change, such as Bruce Springsteen, Bono, or M.I.A., whose “Paper Planes” samples the Combat Rock cut ”Straight to Hell,” cite Strummer or his band as a key inspiration.

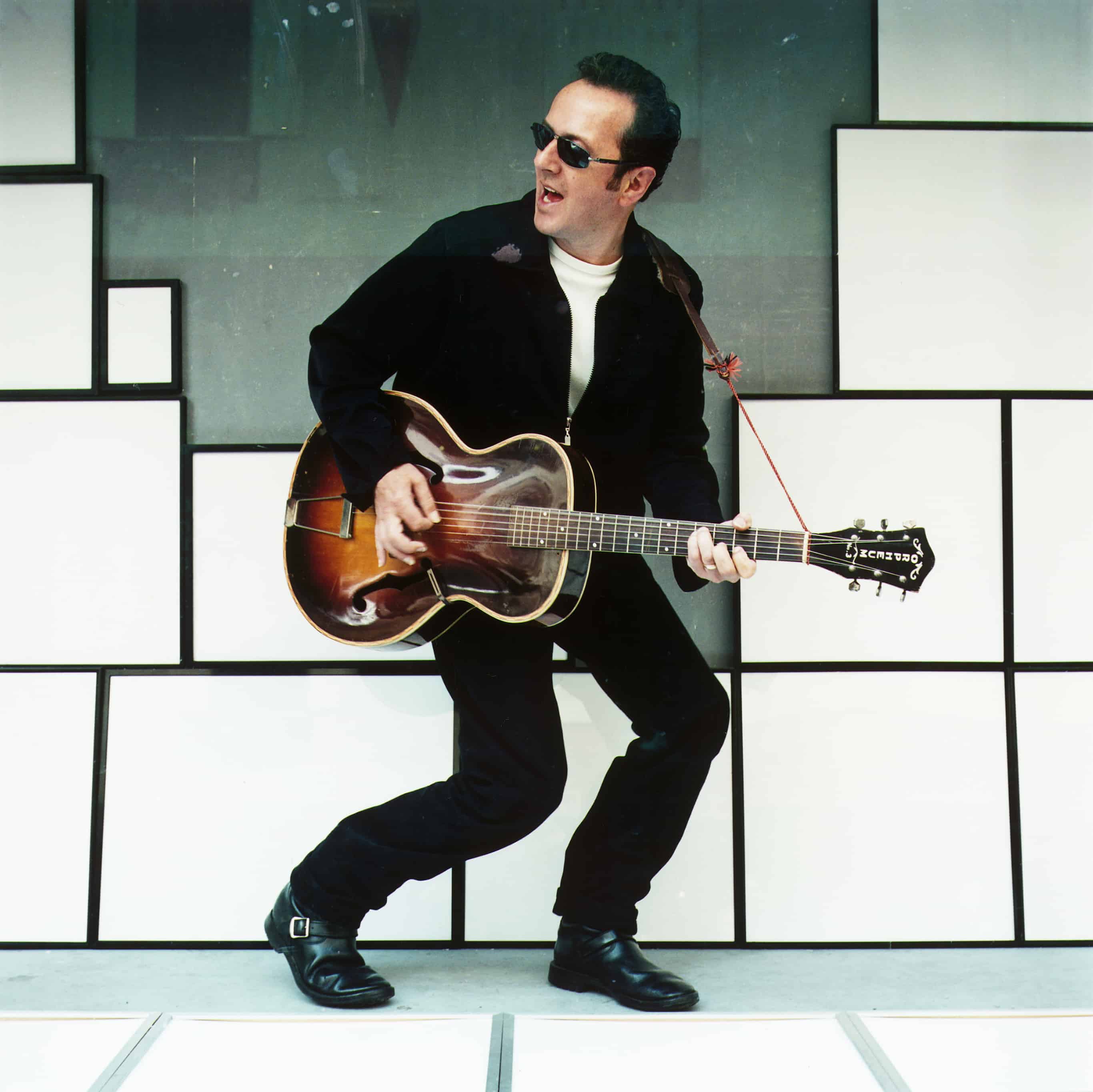

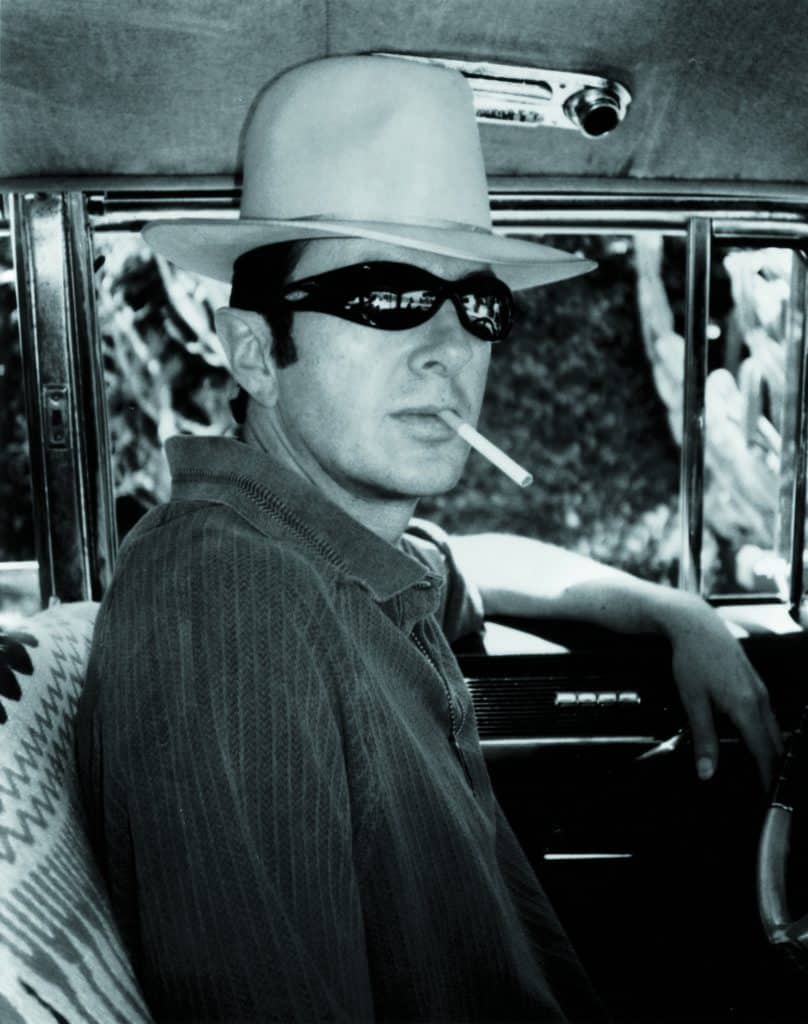

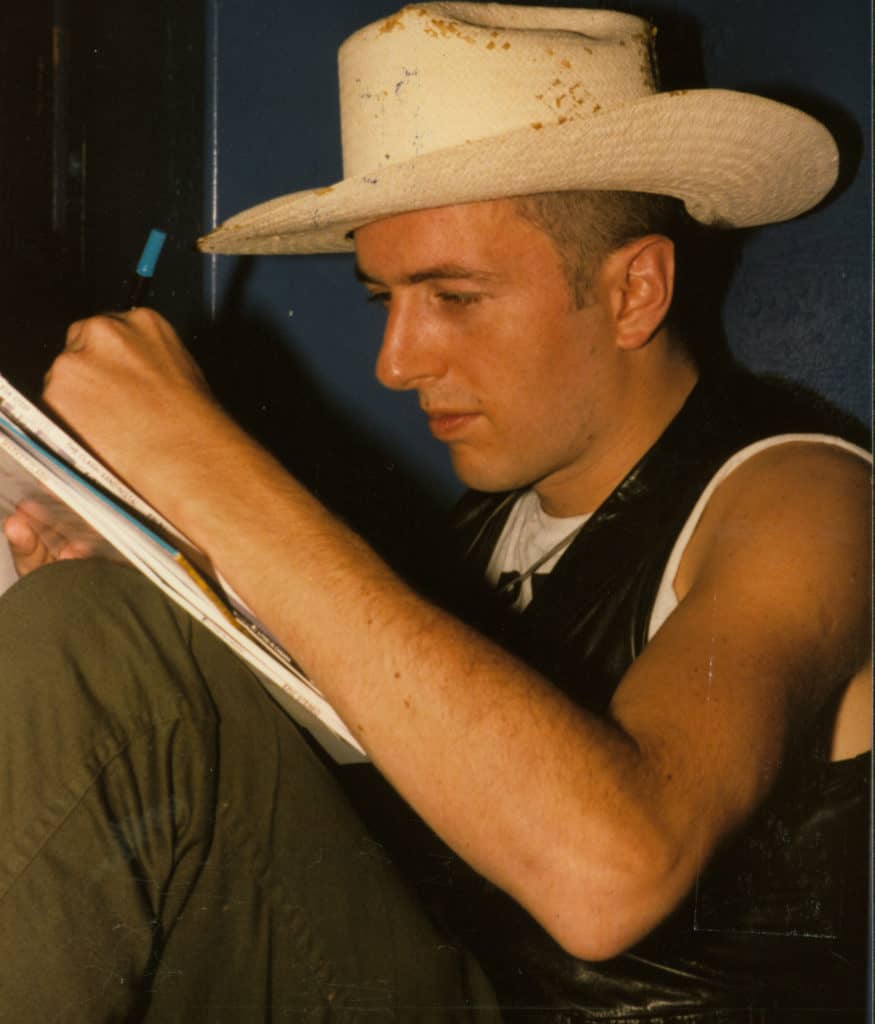

While many books, documentaries, and box sets are dedicated to the Clash, Strummer’s work outside the band has long been overshadowed by the more incendiary work he recorded with Jones, bassist Paul Simonon, and drummer Topper Headon. That’s to be expected, as the Clash cut eight LPs worth of music in just six years, much of it touched by Strummer’s mix of earnestness and bravado. Yet a new compilation, Joe Strummer 001, sheds light on Strummer’s solo work and, in turn, serves to further illustrate how and why his legacy endures.

There’s a wide range in tone and sound, as the jaunty, loving, and little-heard “When Pigs Fly” contrasts with a starkly resonant duet with Johnny Cash on Marley’s moving, end-of-life tale of personal freedom, “Redemption Song.”

For those who aren’t Clash diehards, most of the songs on Joe Strummer 001 will likely prove unfamiliar. There’s a wide range in tone and sound, as the jaunty, loving, and little-heard “When Pigs Fly” contrasts with a starkly resonant duet with Johnny Cash on Marley’s moving, end-of-life tale of personal freedom, “Redemption Song.” The more than 30 songs on the box set see Strummer not only experimenting regularly with the island-inspired sounds he favored in the Clash, but also touching on new-wave and, later, digital textures.

Some experiments fare better than others. The trite rave-up “It’s a Rockin’ World,” recorded for South Park, is a throw-away, and a cover of the reggae tune “Ride Your Donkey” feels present just so the set could represent something from Strummer’s forgettable 1989 solo effort Earthquake Weather. But they prove the exceptions on a collection that reflects an artist whose work not only possesses a curiosity toward the sounds of different cultures but an underlying belief that music could be a source for optimism in an often-challenging world.

While Jones went on to limited success with the dance-leaning rock band Big Audio Dynamite, Strummer was largely considered missing in action in the years following the Clash’s split. (Strummer recorded one Clash album without Jones, 1985’s Cut the Crap, which he immediately disowned.) Yet until Strummer formed the Mescaleros in 1999, his output remained relatively erratic, appearing largely on soundtracks.

Those hoping for a Clash reunion were teased, briefly, when Strummer and Jones patched up their relationship to collaborate on Big Audio Dynamite’s 1986 album No. 10, Upping St. The reformation didn’t occur, but a little-known Strummer-Jones tune, “US North,” recorded in ‘86, surfaces on Joe Strummer 001. While its spritely synthesizers and choppy guitar work probably don’t warrant the 10-minute running time, it’s a joy to hear, largely due to the mesh of Strummer and Jones’ vocals—the latter coarse and roughed-up and the former bright and clear.

The Clash wrote unabashedly about Hollywood (see the tragic story of actor of Montgomery Clift in “The Right Profile”), and also chronicled how pop-culture de-sensitized people to the headlines of the day (see “Magnificent Seven” and its references to news as entertainment).

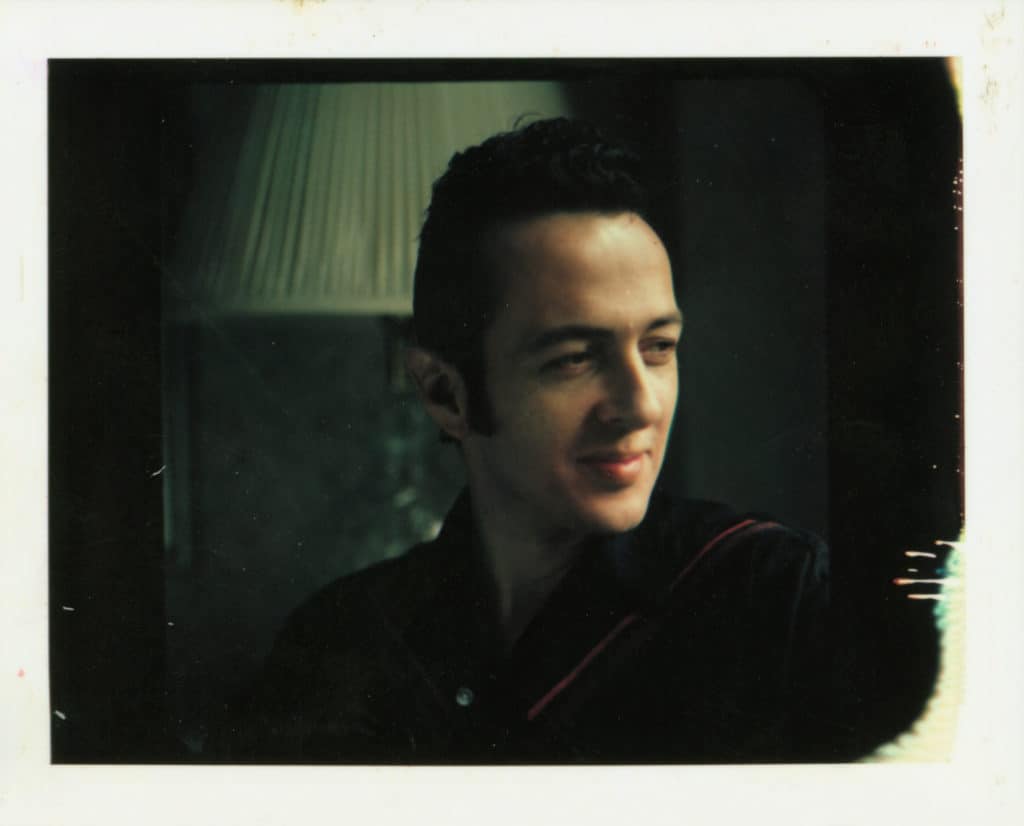

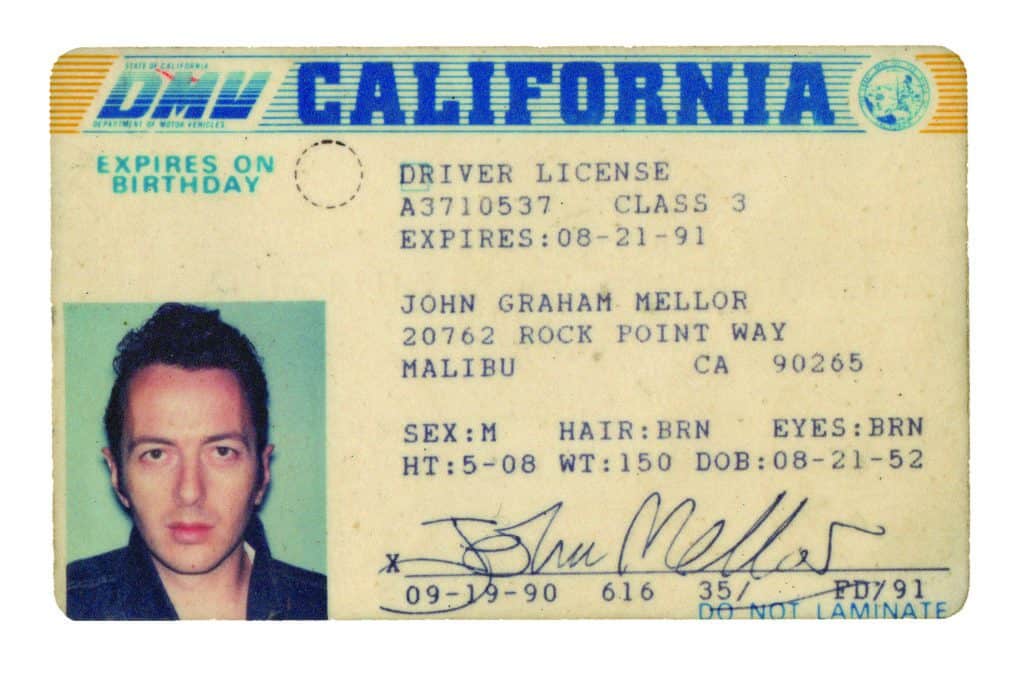

While few will count “US North” among their favorite Strummer-Jones compositions, it hints at what was lost when the pair split. Strummer brought a bit of bite to Jones’ pop-leaning songs, and Jones gave Strummer’s penchant for recklessness and global sounds a melodic core. Which helps explain why Strummer, born John Mellor in Turkey to a nurse mother and a father who was an English diplomat, always appeared more open in interviews to a Clash reunion. He recognized Jones had a knack for a hook. Even in punk rock, that’s a form of currency.

In the years that followed the Clash’s split, Strummer appeared to zero in on another of his other passions: cinema. The Clash wrote unabashedly about Hollywood (see the tragic story of actor of Montgomery Clift in “The Right Profile”), and also chronicled how pop-culture de-sensitized people to the headlines of the day (see “Magnificent Seven” and its references to news as entertainment). Then, of course, there’s the band’s 1980 film Rude Boy that, while a slog to watch, boasts some of the most arresting live footage of the band. The Clash was also huge fans of Martin Scorsese, and Combat Rock remains as influenced by Taxi Driver as it is politics.

While Strummer often struggled to get a new band off the ground—even the Mescaleros were formed initially for soundtrack work—films energized him. “Love Kills,” recorded for the 1986 Alex Cox movie Sid and Nancy, even feels cinematic in its approach. Rather than focus on the story of Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen, Strummer pens an outlaw tale: one of passion-fueled horrors that dips and rages as its antagonist crossed borders. Meanwhile, the song’s aggressive guitar work obliterates the steady, synth-fueled rhythms, illustrating Strummer’s penchant for new sounds and technology rather than staying the course.

A number of tracks on Joe Strummer 001 are culled from now hard-to-find or out-of-print soundtracks. Keanu Reeves’ 1988 film Permanent Record is largely forgotten, but Strummer’s ramshackle “Trash City” comes across as delightfully rough, full of colorful lyrics like “wanna see a movie ’bout a creeper on the house” and “making love in the graveyard with cockroach bones.” While Strummer and the Clash always seemed willing to stretch boundaries and genres, soundtrack work appeared to allow Strummer to try on different characters—the rootsy honky-tonk of “Pouring Rain 1984” (from When Pigs Fly) or the nostalgic ballad of “Burning Lights” (from I Hired a Contract Killer).

There’s also an unheralded quality of Strummer’s work: his lyrics. Even as he often led with emotion— see Clash songs “I’m So Bored with the U.S.A,” a screed against American pop art, or “White Riot,” a not-very-thought-out call for a revolution—Strummer also harbored a penchant to write about people rather than a situation. The Clash song “Bankrobber” is essentially a character study about a kindhearted criminal and “White Man in Hammersmith Palais” relates to the haves and the have-nots that asks listeners to get out of their comfort zones.

His late-career work included on Joe Strummer 001 continues on such a track. “Generations,” recorded for a benefit album, doesn’t preach but paints a picture of an adult buying clothes for a child only to then realize the conditions in which those clothes were made. “Yalla Yalla,” his first proper single with the Mescaleros, peppers a reggae groove with alien effects while the song’s characters struggle to not let life knock the rebellion right out of them.

And the jerky guitars of “London Is Burning,” one of Strummer’s last songs and one of his loudest, contrasts two visions of the city and contains a haunting line: “Too many guns in this damn town/At the supermarket, you gotta duck down.”

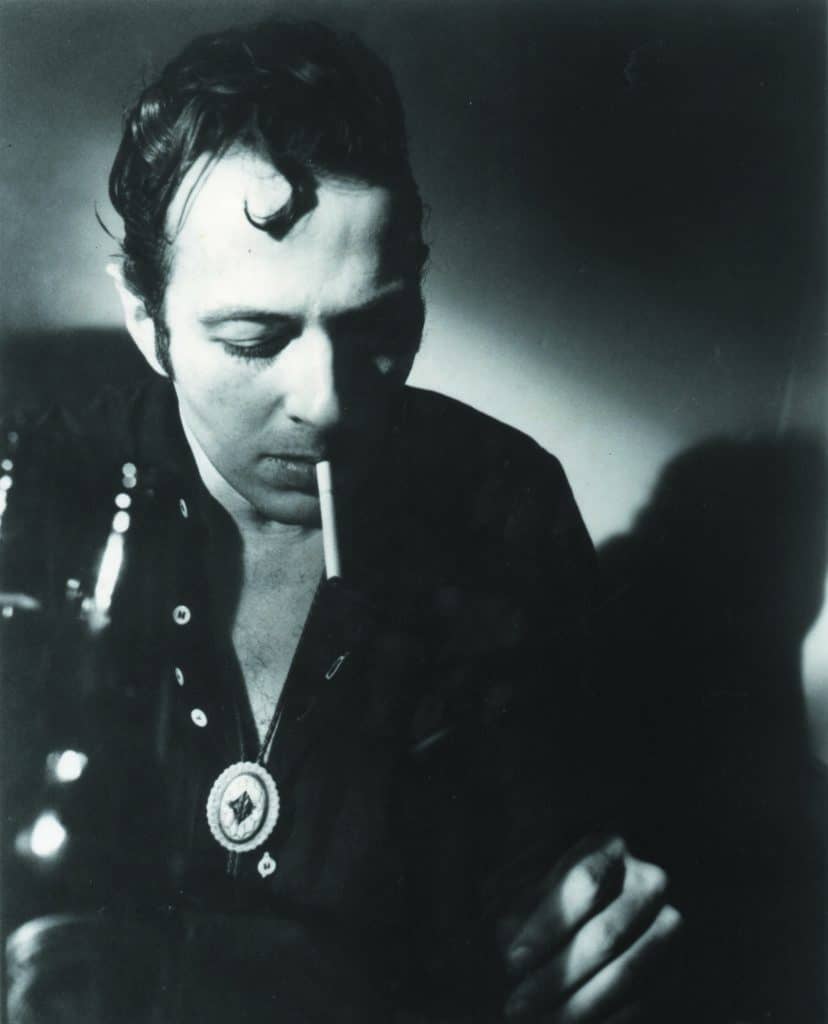

Evocative, yes, but also full of passion. Often, people speak of Strummer the performer—the singer always drenched in sweat two or three songs into a set and standing before the microphone as if electric currents coursed through his body. Yet the major appeal of Joe Strummer 001 relates to how it showcases the less-heralded aspects of the artist, portraying him with a lust for cinema, a widescreen approach to musical styles, and a flair for imaginative lyrics.

Just listen to “Coma Girl,” a love letter to his daughter, which teems with wild characters: a “motorcycle gang,” an “oil drum gang.” The scene is a music festival, but Strummer puts us in a sci-fi film. No wonder, then, that Strummer’s words manage to resonate in political debates in 2018. When someone like Rollins says, “This is what Joe Strummer trained you for,” he’s referencing much more than Strummer’s anger, principles, or revolutionary yell. For in the Clash and beyond, Strummer never wavered in his belief that the world could not only be a better place, but a vibrant one as well.

4

4