Marketplace

2018 Zappa Records PRESSING

- Catalog Number ZR-3842-1

- Release Year 2018

- Vinyl Mastering Engineer Bernie Grundman

- Pressing Weight 180g

- Jacket Style Gatefold

- 100% Analog Mastering Yes

- Pressing Plant Pallas

- Original Release Year 1970

- Original Label Bizarre/Reprise

- Original Catalog Number RS-6730

When listening to this album I think of this band or music:

Frank Zappa’s music, as unique as it was, drew from many influences. On this album, I hear the impact of his interest in modernist composers such as Stravinsky and Varèse. Here, he successfully integrates their ideas with rock, jazz, and other genres.

Music from this album would be a great soundtrack to this movie:

I could hear “Theme from Burnt Weeny Sandwich” paired with a city scene in a strangely off-center mystery set in the late 60s. The solo piano opening of “Little House I Used to Live In” would fit into a domestic drama staged in a cold climate. Both parts of “Igor’s Boogie” would fare nicely in a dark comedy set somewhere in Europe during the 30s.

Frank Zappa released Burnt Weeny Sandwich after he dissolved the original Mothers of Invention. The album consists of studio and live recordings the band made dating back to 1967. Zappa and his fellow musicians overdubbed additional instruments on some tracks, but the result still presents a clear picture of what the Mothers were doing after four years of recording and five LPs. Although the effort contains motifs and techniques Zappa explored on Lumpy Gravy (1967) and Uncle Meat (1969), Burnt Weeny Sandwich feels more focused—in part because it dispenses with the spoken-word parts present on the other two aforementioned recordings.

I’ve owned several copies of Burnt Weeny Sandwich, including an early tri-color steamboat Reprise pressing from the U.K. and a Simply Vinyl pressing from 1998. But my favorite was the original Bizarre Records release from 1970. It features tremendous low-frequency energy and enough spatial detail to convey the complexity of Zappa’s compositions.

Indeed, I have long used the closing moments of “Holiday in Berlin, Full Blown” to evaluate speakers. Zappa’s guitar solo plays against the sharp snap of two snare drums and the hard thump of kick drums. The original LP presents such details with more force and detail than the other pressings. I always expect a pair of speakers to accurately present these aspects.

Bernie Grundman’s all-analog master for the new Zappa Records reissue, cut from a 1970 analog safety master, retains much of the low-frequency energy of the original but presents a cleaner top end that renders horns, keyboards, and drums more clearly and with added realism and accuracy. The martial drums on “Holiday in Berlin, Full Blown” feel more forceful and three-dimensional, and the aforementioned kick-drum thump remains strong even as the arrangement’s complexity and percussion interactions more strongly register. Zappa’s guitar solo is also much more clearly delineated; you can picture his picking technique.

On this pressing, cymbals splash with more force and hang in the air long longer, keyboards are easier to hear, and tiny bits of percussion reach out of the soundstage. The notes on Ian Underwood’s piano solo on “Little House I Used to Live In” carry more weight, and the piano itself sounds multi-dimensional. The organ and horns that enter after Underwood’s introduction get more room to blossom and catch your ear. Don “Sugarcane” Harris’ violin solo possesses more grit and texture, and its interaction with other instruments is more fleshed out.

As a whole, the reissue proves more transparent and presents the music on a deeper soundstage than the original. I can now really appreciate how much care Zappa took with the vocal arrangements on the doo-wop tunes that open and close the album, and remain surprised by the new things I hear in a record I’ve owned for more than 40 years.

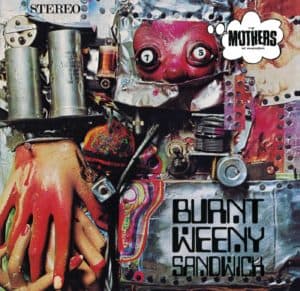

The pressing, by Pallas in Germany, is first-rate—utterly silent and flat. The cover art is equally well-rendered, and includes the poster that came with the original pressing. Bernie Grundman has remastered several Mothers of Invention recordings for vinyl, as well as some of the maestro’s solo work. This LP represents the kind of care merited by Zappa’s work.

Burnt Weeny Sandwich

4.5

4.5