Marketplace

2018 Bad Boy Records PRESSING

- Catalog Number 567348-1

- Release Year 2018

- Vinyl Mastering Engineer Dave Kutch

- Pressing Weight Regular Weight

- # of Disks 2

- Jacket Style Gatefold

- 45 RPM Yes

When listening to this album I think of this band or music:

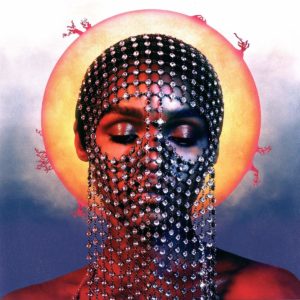

Fans who have been with Janelle Monáe since the beginning may expect the outlandish, the wild, and the sometimes a bit crazy. Her musical world is one of outsiders and misfits, but also androids and intergalactic visions. It fits into an R&B tradition that nods to the spaceflight metaphors of George Clinton, but also lands periodically in the universes of OutKast and Prince, the latter a regular collaborator to whom Monáe dedicates the album.

Here, she streamlines. The aforementioned influences arise, but Monáe thinks big – pop-star big. Dirty Computer doubles as a call to a revolution, sexual and political, and aims to amass an army by taking over the dance floor. Her vision has room for the psychedelic warmth of Brian Wilson, the futuristic dance of Grimes, and the large-scale embrace of Pharrell Williams.

Music from this album would be a great soundtrack to this movie:

Monáe’s music deserves the silver screen, and the record is so vivid, colorful, and accessible, it would be a shame if anything from Dirty Computer appeared in a creation not written, conceived, and directed by Monáe. While Dirty Computer and 2013’s The Electric Lady appear more earthbound than her initial works—her 2007 EP Metropolis introduced the planned seven-part storyline of the sent-from-the-future Cindi Mayweather—Monáe still mixes up the personal, the political, and the sci-fi.

She also has big-screen ambitions. Early in Dirty Computer she sings, “Jane Bond, never Jane Doe, and I Django, never Sambo,” tossing out a few movie references that not only imagine a female-identifying hero but also acknowledge Hollywood’s checkered past when it comes to putting diverse voices in starring roles. Until someone gives Monáe a development deal, let’s imagine her songs gracing a better version of Atomic Blonde, the 2017 action thriller that stars Charlize Theron as a weaponized human.

“We ain’t hiding no more,” Janelle Monáe sings on “Django Jane,” a slow-bumping, bass-heavy tune that arrives halfway through the album. A screed against how women and people of color have been written out of mainstream media, it references her role in the Oscar-winning film Moonlight and goes on to say she’s gunning for a Grammy.

Dirty Computer, which ended up garnering a Grammy nod for Album of the Year, among other nominations, isn’t an effort one should bet against. Few works in 2018 so seamlessly melded the topical with the approachable. The finger-snapping charm of “Pynk” stands as a celebration of all-things-female, while “Screwed,” with its funky, light-stepping guitar notes, uses sex as a metaphor for oppression and liberation, all while offering a forthright message to any doubters: “We’re gonna crash your party.”

Monáe gets more explicit on “Americans,” with neon-coated keyboards gracing what could essentially be a political speech: Monáe pledges allegiance to everyone without a voice. She gets extra personal in “I Like That,” recalling an instance of high-school bullying due to the color of her skin and her family’s income, and turns the memories into a statement of power. “I’m the random minor note you hear in major songs,” she declares, while swooning, Motown-worthy harmonies turn the cut into a love letter for weirdos.

Such spirit embodies the heart of Dirty Computer. Monáe may not like what she sees in 2018, but she’s here to recruit, not to fight.“I’m not America’s nightmare,” she sings on “Crazy, Classic, Life” amid uplifting synthesizers and triumphant hip-hop beats. “I’m the American dream.”

The two-disc vinyl edition of Dirty Computer arrived about five months after the album’s initial release, and the 45RPM release proves worth the wait. The gatefold sleeve, boasting more of Monáe’s retro-futurist art, holds poly-lined vinyl sleeves and a double-sided credits page. While the package eschews lyrics, Monáe offers inspiration for the songs.

What’s surprising is just how wonderful it all sounds, especially considering the record is a pop-focused major label release. Dirty Computer plays as one of the quieter mainstream pressings we’ve heard this year, and the balance between the often-booming bass and the bright, kaleidoscope-like synthesizers feels entirely on point. The low-end never overpowers, and every deft, shimmering touch of the arrangements gets a moment to shine. It all feels beautifully decadent and incredibly rich, with even the seemingly most minor of notes treated with reverence.

Dirty Computer

4.5

4.5