Marketplace

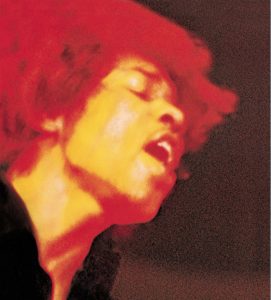

2010 Sony Legacy Recordings PRESSING

- Catalog Number 88697 62398 1

- Release Year 2010

- Vinyl Mastering Engineer George Marino

- Pressing Weight 180g

- # of Disks 2

- Jacket Style Gatefold

- 100% Analog Mastering Yes

- Original Release Year 1968

- Original Label Reprise

- Original Catalog Number 2 RS 6307

When I listening to this album I think of this band or music:

Jimi Hendrix toured with R&B musicians early in his career, including the Isley Brothers and Curtis Knight. Electric Ladyland shows a more pronounced soul influence than his first two studio recordings. I hear a bit of Curtis Mayfield on the title track, and other R & B techniques are clear in the backing vocals throughout the album and in Hendrix’s rhythm guitar playing. I also think of Bob Dylan because of Hendrix’s definitive interpretation of “All Along the Watchtower.”

I would listen to this album while:

This album still demands my undivided attention, even after listening to it for nearly 50 years. In some ways, it remains the most layered and subtle of Hendrix’s recordings—and because of its length and variety, I still find much to hear. The mystical Hendrix is in “1983…A Merman I Should Turn to Be,” Hendrix the blues musician is incredibly present in “Voodoo Chile,” and the artist who transcends description is in “All Along the Watchtower” and every other track.

Music from this album would be a great soundtrack to this movie:

“House Burning Down” would make a tremendous addition to a movie about the rise of African-American political activism in the late 60s. “All Along the Watchtower” would also place the film in time in much the same way. I hear “Burning of the Midnight Lamp” in a strange sci-fi movie.

Electric Ladyland stands as the last album Jimi Hendrix recorded with the Experience, and the last studio effort released in his lifetime. It’s also the only album he produced himself. It shows a pronounced R & B influence— emphatically on the title track—but also in Hendrix’s choices in other areas of the record, such as the backing vocals on “House Burning Down.” The set charted at #1 in the U.S., and one of the singles, a cover of Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower,” gave Hendrix his sole Top 40 hit in the U.S.

Hendrix also brought in some guest musicians, including the Jefferson Airplane’s Jack Casady and Traffic’s Steve Winwood, both of whom play on “Voodoo Chile.” For the most part, however, the tracks are by the Experience, which plays in a wide variety of styles. As with many double albums, it’s tempting to say some editing would have led to a stronger single record, but it’s hard to think of anything to cut. Everything here contributes to a better understanding of Hendrix’s towering greatness.

George Marino’s all-analog mastering of Hendrix’s recordings have the clarity and drive of his 1997 vinyl cuts of the recordings, which were sourced from high-resolution digital files. My main source for comparison is a 1972 Reprise U.S. pressing, which I still prefer overall to the 1997 release because of its analog warmth.

The tape-manipulated, slowed-down drums that open the album on “And the Gods Made Love” feature tremendous, expansive force on the 2010 master. Other effects on the track take place on a deeper soundstage that creates the illusion of the sound being in front of and behind the speakers—as well as side to side. On the earlier pressing, the effects seem to stop at the speakers. Hendrix’s strikes against the guitar strings leading into “Have You Ever Been (to Electric Ladyland)” are more sharply present in the newer pressing, with a more pronounced high-end ring.

Compared to those on the new pressing, his vocals also sound flat on the 1972 LP. You can now hear how accomplished he was as a soul singer on “Have You Ever Been (to Electric Ladyland),” and the vocals throughout the album come across with more detail, giving a better picture of his emotional commitment to the songs. Backing vocals are also more layered and richer throughout.

“Crosstown Traffic” is more muscular on this pressing, and the guitars more slashing and bright. Casady’s bass on “Voodoo Chile” is more defined and forceful, and Steve Winwood’s Hammond B3 lines emerge with greater conviction. Small details, such as the reverb on Hendrix’s guitar and the attack of his pick against the guitar strings, stand out more, and the notes sustain longer.

By extension, Mitch Mitchell’s drums feel even more explosive on “All Along the Watchtower” on the newer pressing, and you can clearly hear the chords on Dave Mason’s 12-string guitar. The electric harpsicord on “Burning of the Midnight Lamp” is more sharply focused and better plays against Hendrix’s guitar. And the intro to Earl King’s “Come On (Part 1)” rips harder than on the earlier pressing. In short, Marino gives listeners a more transparent picture of what Hendrix and his collaborators were doing in the studio.

I have an affection for my earlier pressings of Hendrix’s LPs after more than 40 years of listening to them, but the pressings cut from Marino’s 2010 masters are sonically more exciting and are the ones to which I now turn.

Electric Ladyland

4.5

4.5