Marketplace

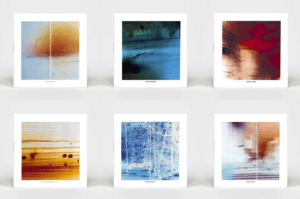

2018 Newvelle Records PRESSING

- Catalog Number NV 013-18LP

- Release Year 2018

- Vinyl Mastering Engineer Alex DeTurk

- Pressing Weight 180g

- # of Disks 6

- Vinyl Color Clear

- Box Set Yes

- Jacket Style Gatefold

- Pressing Plant MPO

When listening to this album I think of this band or music:

The care and thoughtful design of these records reminds me of a series of electro-acoustic LPs released by Philips beginning in 1967 under the name “Prospective 21˚Siēcle.” The short-lived series featured covers printed with metallic inks, silver foil, and abstract designs. Like those of Newvelle, the LPs were very well recorded.

Music from this album would be a great soundtrack to this movie:

This kind of haunting, ethereal music brings to mind the mood of a Jim Jarmusch film, especially Stranger Than Paradise. Unlike that movie’s protagonists, however, the artists here do not work hard to make the least of any opportunity. This is minimalism at its best.

Marketing LP records has dramatically changed from the 1970s, when records were sold by mail through record clubs like Columbia House and Record Club of America. They tried (unsuccessfully) to break the stranglehold of brick-and-mortar stores by selling direct. With clubs not affiliated with a label, like Record Club of America, you could always count on pretty gruesome cover artwork. With company affiliates like Columbia House, you would get decent-quality covers but a record-club pressing that almost always turned out to sound worse than the regular run. The clubs also practiced predatory marketing practices. A low loss-leader price sucked you in but the small print required you to opt out of regular purchases on short notice, and you almost always ended up buying records you didn’t want.

Now in its third year, Newvelle Records is releasing subscription LPs employing a very different direct sales approach. Rather than shoot for high sales volume, Newvelle LPs are intended to be collectible—a physical object that begs to be handled with attention. The imprint’s artist roster is phenomenal—you’d think you were buying from Blue Note or ECM rather than a start-up. And the physical presentation is as good as it gets. Each LP receives a foldout cover with artwork commissioned from well-established artists. Covers minimize the amount of notes in favor of ceding space to art and poetry.

Season Three covers feature lavishly printed photography from Polish artist Maciej Markowicz with text from French author Ingrid Astier, who tells a story in six “chapters.” Further technical details are found online. The choice of clear rather than black vinyl adds a touch of singularity. A season lasts a year, with a record mailed out every two months. At the end of the cycle, Newvelle ships a handsome slipcase box to hold the six records. Unlike record clubs of old, Newvelle charges for quality: A boxed season set costs $400.

The third season presents a broad selection of small-group acoustic music played by an amazing cast of musicians. While Newvelle’s founders stem from Paris, and its records are pressed in the E.U., the third installment celebrates New York’s progressive jazz scene. A healthy blend of recognizable names plays alongside top performers who have not yet established themselves as leaders. The music’s overriding mood is atmospheric and dreamlike, but never boring. With few exceptions, the fare proves more introspective than most jazz up through the 1960s.

The first LP, Charlie & Paul, serves as a tribute to Charlie Haden and Paul Motian played by four musicians (Steve Cardenas on guitar, Loren Stillman on alto saxophone, Thomas Morgan on bass, and Matt Wilsonon drums) who knew both and played in the veterans’ groups. The Cardenas LP sets a trend by refusing to lock on to a harmonic framework, demanding the listener keep up with the instrumentalists.

Tenor saxophonist Andrew Zimmerman—joined by Dave Douglas on trumpet, Kevin Hays on piano, and Matt Penman on bass—leads Half Light, the second LP of the series. Zimmerman, in his first session as a leader, played with Douglas before, and the setincorporates the latter’s signature ruminative approach. The session of compositions skews in dreamlike directions but avoids new-age noodling.

Lionel Loueke, a guitarist who has led a dozen sessions over the last 15 years—and played on recordings by Haden, Herbie Hancock, Terence Blanchard, and Wayne Shorter—leads Close Your Eyes with Reuben Rogers on acoustic bass and Eric Harland on drums. Loueke, the least-atmospheric sounding (and least acoustic) player in the season’s mix, steps out of his comfort zone and delivers his first all-standards set. Up fourth is Strata, with duets from guitarists Skúli Sverrisson and Bill Frisell playing songs written by the former for the latter. The two have never played together before yet sound as though they’ve been doing so for years. It registers as a performance and a nice break from Frisell’s wonderful Americana albums.

Francisco Mela commands Ancestros from his drum kit, alternating solos with horn man Henry Pazand pianist Kris Davis. Double bassist Gerald Cannon lends rhythmic support. Paz opens the album on bass clarinet that he rotates with tenor and soprano saxophone. Finally, trumpet player Jason Palmer directs Leo Genovese on piano, Joe Martin on bass, and Kendrick Scotton drums in Fair Weather. Palmer has released a series of well-received CDs for the Steeplechase label. The session feels more cerebral than the other performances here and, at times, Genovese, a sideman for Esperanza Spalding, occasionally commandeers the proceedings on the otherwise thought-provoking journey.

Newvelle takes audio quality seriously and it shows. The label’s recordings are made at East Side Sound in New York City by engineer Marc Urselli. The ultra-high-quality recording chain involves a Harrison Series Ten B analog console, mostly vintage and some tube microphones, and all-analog and tube preamplifiers. Pro Tools HDX is also used, and the recordings are captured in high resolution—never less than 24-bit/88.2kHz. Alex DeTurk of Masterdisk oversees mastering and cuts the lacquers from the high-resolution mixes. Newvelle’s vinyl gets pressed in the E.U. The results—on this season and the preceding two—amount to some of the best-sounding jazz LPs around today. While they lack the ultimate atmospheric feeling of a vintage all-analog session recorded at Columbia’s 30thStreet Studio in the late 1950s, they achieve clarity of instrumental detail and weight missing from golden-age recordings—an ideal melding of old and new.

Enter to win the Season Three Newvelle Record Box Set

Newvelle Records Season Three

4.5

4.5