Marketplace

2018 dBpm Records PRESSING

- RPM 33 ⅓

- Audio Stereo

- Catalog Number DBPM – 007 – 18 - LP

- Release Year 2018

- Pressing Weight Regular Weight

- Jacket Style Single

- Pressing Plant MPO

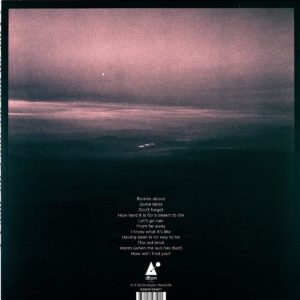

Warm may at first appear relatively slight. While Wilco’s Schmilco is also largely acoustic—so much so that when an electric guitar appears, it sounds bracing—the album conveys an underlying sense of passive aggressiveness that leans toward disquieting. Here, however, Tweedy opts for a more direct lyrical approach, and the arrangements have a softer, less biting tone. Not until the fourth song, “How Hard It Is for a Desert to Die,” do we uncover any of the atmospherics in which Wilco specializes. On the track, rhythms shiver and the twisted notes of a lap steel break the album out of its initial jangly groove.

The informal quality reflects Tweedy’s less-heralded side, one largely appreciated by his diehard fans. While some of the singer’s solo excursions can feel a bit unnecessary—see last year’s drab Together at Last, full of re-recorded works originally meant for Wilco and Tweedy’s other projects—his solo tours tend to be colloquial gatherings that double as conversations with the audience. Onstage, he presents music as comfort, with the impressive musicianship of Wilco replaced with a cozy levity.

Such ease permeates Warm, an album that not only reflects Tweedy’s age (he’s 51) but sees the artist singing more informally about life and death. The strongest moments, such as “Don’t Forget,” teem with contrasts. “Don’t forget,” Tweedy sings, that sometimes “we all think about dying.” A few seconds later, however, he adds, “Don’t forget to brush your teeth.” And when he envisions his own funeral on “From Far Away,” he pleads to those still living to “take my books and my magazines and my photographs.” These moments witness Tweedy balancing life’s regrets and challenges with everyday worries—all of which in the course of 24 hours can become all sorts of mixed up.

As the album unfolds, things turn bleaker. “The Red Brick,” for instance, begins with an urgently strummed guitar and more forceful vocals. Gone is the raspy, good-natured singer. Tweedy takes a more aggressive tact on a work haunted by memories, and one that explodes in a finale of feedback and fuzz. “How Will I Find You” evolves into a six-minute dirge built around Kotche’s pounding heartbeat of a rhythm. “Having Been Is No Way to Be” veers from the set’s lyrical brevity to spin a wordy tale in which Tweedy appears suspicious of everyone. And yet the song can’t help but recognize the value of connection, be it with another person or a song. “I’m still here when you wake up to me,” Tweedy sings, as the tumbling ditty comes to a close.

The release of Warm coincides with Tweedy’s autobiography, Let’s Go (So We Can Get Back). Early in the book, Tweedy talks about his love of music. So perhaps it’s no surprise the Bob Ludwig-mastered Warm sounds terrific (Ed note: while Ludwig mastered the digital files the vinyl is sourced from, the vinyl-cutting engineer isn’t named in the album credits). The album, produced by Tweedy with Tom Schick, emphasizes closeness, and the pitch-black backgrounds of the LP pressing allows us to hear simple hand-taps on an instrument with clarity. Songs such as “Bombs Above” and “Warm (When the Sun Has Died)” rank among the quietest on the record. No interference comes between the listener and the twilight guitar notes.

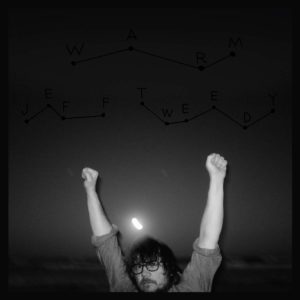

Somewhat subpar, the thin single-jacket package features thick-paper stock for the inner sleeves. Tweedy includes lyrics and a two-page essay from writer George Saunders. Pictures are spare and few, and no one will stare long at the cover art depicting Tweedy’s arms up in celebration. The implication: Words and music are what really matter here.

Warm

3.5

3.5