Marketplace

2018 Intervention Records PRESSING

- RPM 33 ⅓

- Audio Stereo

- Catalog Number IR-028

- Release Year 2018

- Vinyl Mastering Engineer Kevin Gray

- Pressing Weight 180g

- Jacket Style Single

- 100% Analog Mastering Yes

- Pressing Plant RTI

- Original Release Year 1971

- Original Label A&M Records

- Original Catalog Number SP-4292

The middle 1960s produced two fascinating bands linked by their aviary names—the Yardbirds and the Byrds. The former gave early exposure to three of rock’s greatest guitar players, with Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Jimmy Page going on to establish their places in the rock firmament and the balance of the band disappearing with scant trace. The Byrds, on the other hand, generated one player (David Crosby) who achieved massive popular success and three extremely talented musicians (Gene Clark, Chris Hillman, and Jim McGuinn) who never reached the notoriety their gifts suggested they deserved.

Clark served as the principal songwriter for the Byrds’ first couple of years, from 1964 into early 1966. He dropped out because, among other things, he ironically suffered from a fear of flying and couldn’t tour with the group. The Byrds ultimately functioned as incubator for royalty of the incipient country rock movement. While all the original members had at least an affinity with country-tinged folk music, Clark and Hillman proved key figures in blending country with rock. And, of course, after Clark’s exit, the Byrds’ Gram Parsons became a significant player in the genre until his early death.

To further place things in context, Clark’s work with the Byrds pre-dated any general recognition and acceptance of mixing country music with rock. It wasn’t until Bob Dylan’s trio of Nashville albums (Blonde on Blonde, John Wesley Harding, and especially Nashville Skyline) and Parsons’ marriage of psychedelia and country in his music (and clothing) that the record buying public grasped what was going on. Clark’s solo debut, 1967’s Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers, is very much in the same vein as the Byrds. The trouble was the Byrds were very much alive and releasing some of their best material, thereby overshadowing Clark. His next outing, a 1968 partnership with Doug Dillard, The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark, brought bluegrass to the fore and received high critical praise. But it barely caught the public’s attention.

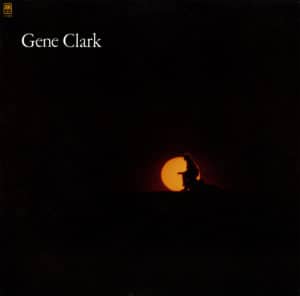

White Light, Clark’s second effort as a solo artist, remains a wonderful singer-songwriter album with a light country influence. Chris Ethridge of the Flying Burrito Brothers, jazz and rock pianist Ben Sidran, drummer Gary Mallaber, organist Michael Utley, and percussionist Bobbye Hall Porter back Clark. The session is best described as intimate. The LP took off with critics but again failed to click with the public. Part of its lack of commercial success owes to the fact the manufacturer forgot to put the album title on the jacket anywhere; only Clark’s name appeared. The back cover featured a photo of Clark looking old beyond his years.

Intervention Records prides itself on releasing somewhat-obscure titles deserving of more exposure—records that give listeners tired of hearing the same old reissued titles a chance to branch out. Company guru Shane Buettner also seems to possesses an ear for finding LPs with hidden charms. This release fits squarely within that model.

Most who listen to an original A&M copy of White Light would not recognize any hidden gold in the master tapes. A comparison with Intervention’s reissue, however, shows otherwise. In the original, the guitars sound almost like toy instruments. There is little texture, which negatively impacts the timing of the music, decidedly sluggish on the original pressing. On the 2011 Sundazed reissue, the guitar sound significantly improves, but the bass guitar seems recessed and out of phase—and the recording still out of time. Intervention’s copy takes a so-so-sounding recording and turns it into a reference-class disc. The recording no longer comes across as torpid and the guitar is full and three-dimensional. White Light finally sounds like music.

*VinylReviews.com is owned and operated by Intervention Records’ Founder Shane Buettner.

White Light

4.5

4.5