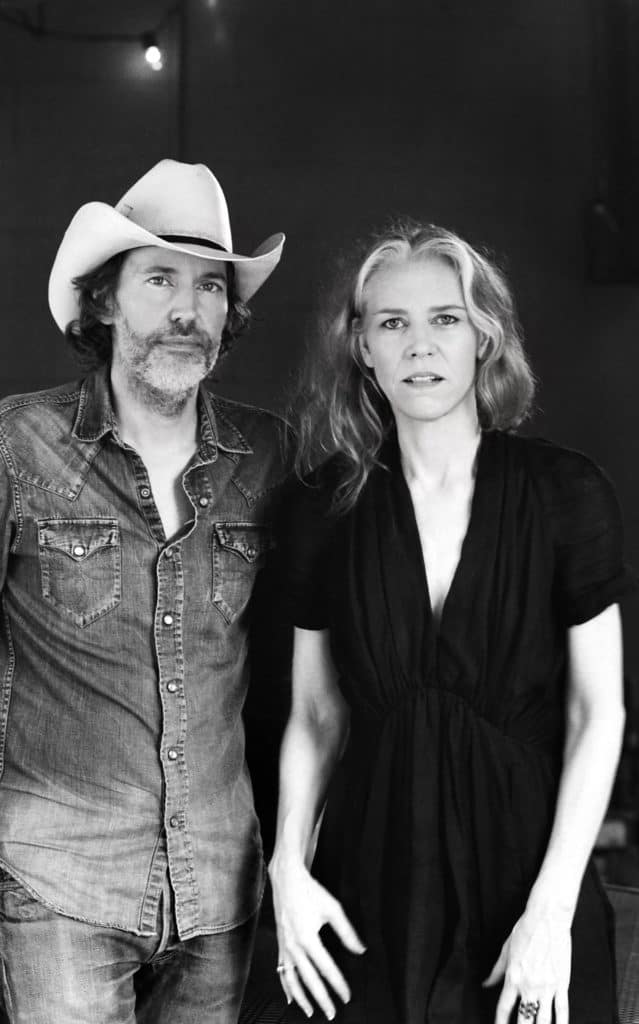

During their preparation to produce Acony vinyl, the pair spent several years and countless hours restoring a Neumann VMS-80 cutting lathe. They paid attention to every detail in the all-analog mastering chain built around it. Rawlings even auditioned different cutter heads to ensure they got the sound they wanted. The lathe now lives in Los Angeles at Marcussen Mastering. But Welch and Rawlings restored some of the individual components in Nashville—including a preview head mod for one the ATR tape decks now part of the vinyl mastering rig—before driving them out to California.

“We’re driving from Nashville to L.A. all the damned time, so we’d fix something and just throw it in the Cadillac,” says Welch.

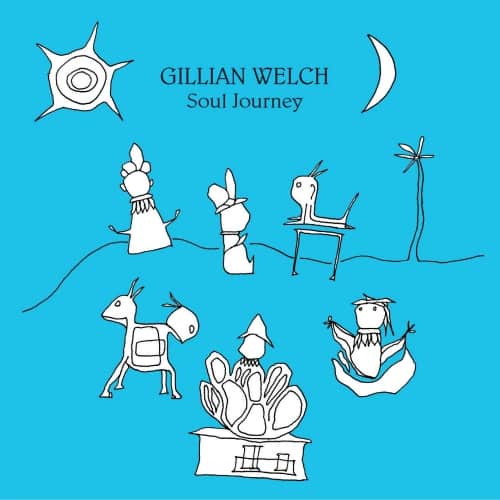

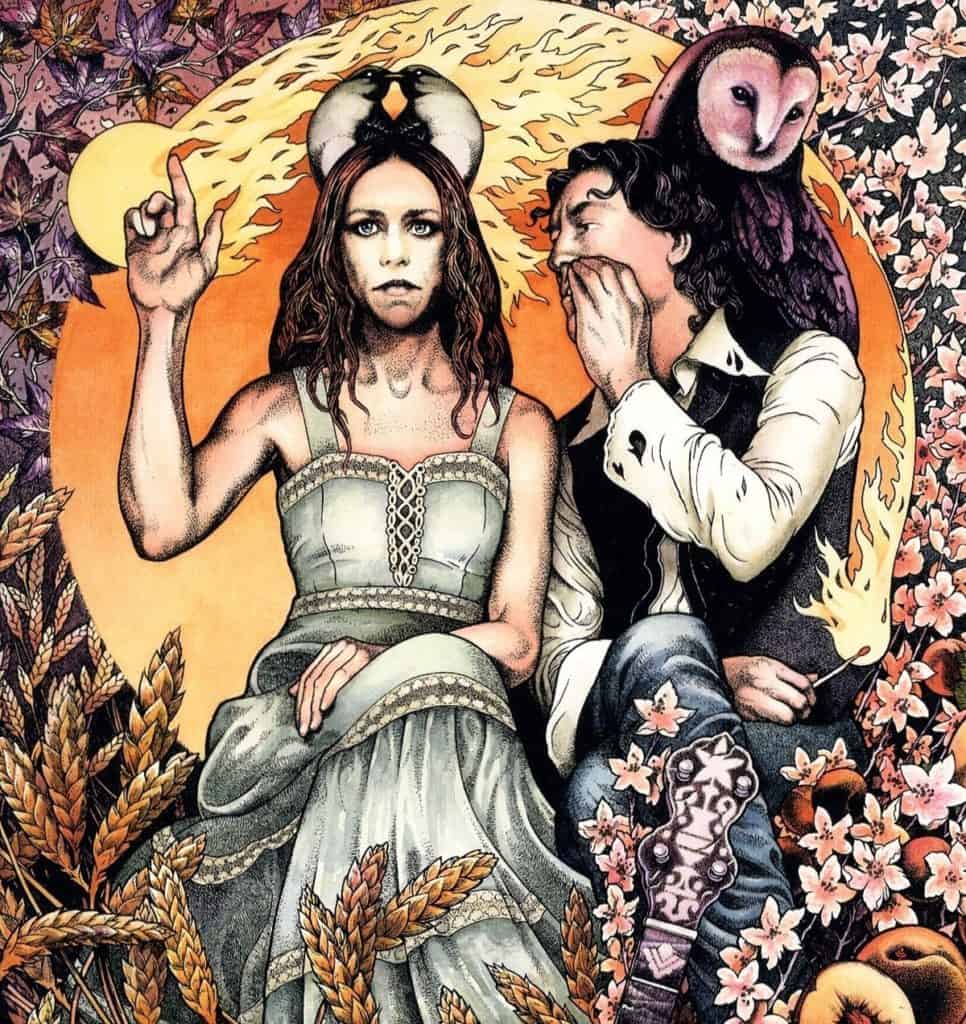

Last summer, all the painstaking labor finally paid off in the form of finished Acony vinyl LPs that both sound and look absolutely spectacular. After beginning with Welch’s 2011 release The Harrow and the Harvest, the label released Rawlings’ Poor David’s Almanack and Willie Watson’s Folksinger Vol. 2. Welch’s 2003 effort, Soul Journey, recently appeared in August.

On Soul Journey, the inner sleeve credits Stephen Marcussen for mastering, which would typically mean he cut the lacquers for the vinyl release. But Acony LPs feature several sets of initials in the vinyl’s dead wax, which is where the real vinyl-cutting credits often reside. Acony’s initial releases are marked “BWRM” for Brent Bishop, Welch, Rawlings, and Marcussen. But the dead wax of Soul Journey reads “BWRMM.”

That’s because the team required another set of hands for tape jockeying. Enter Marcussen’s son, Rufus—and the additional “M” in the runout. Acony’s commitment to excellence truly knows no bounds.

“We don’t want to lose a generation making a tape (or cutting) copy,” says Welch. “Our recordings are on a mix of ½” and 1/4” 15ips and 30ips tapes, and we do our EQ and switch between tapes on the fly (while cutting lacquers). It takes all four of us because we’re switching tape machines and EQ’ing each track while Stephen’s running the lathe.”

Acony’s perfectionist-driven approach doesn’t end once the lacquers get cut. After the latter happens, Acony’s lacquers are sent overnight to Quality Record Pressings’ plant in Salina, Kansas, where they’re plated and processed into metal parts within 12 hours of cutting for the best-possible sound.

The label’s jackets and album art have received just as much attention as the sound. (Stoughton Printing in City of Industry, California, prints the jackets and assembles Acony LPs.) The Harrow and The Harvest and Poor David’s Almanack arrive housed in jackets appointed with beautifully textured, thick paper. For Soul Journey, the original art was restored and the artist handwrote the lyrics for the gatefold.

In addition to releasing new Acony titles on vinyl, Rawlings and Welch will continue reissuing their respective back catalogs in chronological order. Welch’s classic Time (The Revelator) is next on the schedule. And to think all their plans were nearly thrown into jeopardy by a deal outside of their control.

A few years ago, a European label acquired some album rights and had Soul Journey pressed on vinyl sourced from digital files. Welch found out and paid out the contract to have the LPs destroyed.

“It was all legit, through our overseas partner,” she explains. “But we didn’t know about it until the vinyl was pressed. When we found out we contacted them and paid for destruction on all the pressed records. There’s no hard feelings, but we just couldn’t have it.”

Welch’s money-where-her-mouth-is actions reflect an admirable combination of self-determination and steadfast refusal to compromise. It’s a position that merits respect—but demands fans remain patient.

“People used to ask when our music was going to be on vinyl,” Welch says, “and I just couldn’t convey my depth of longing for good vinyl of our records. It’s taken us around eight years total, but it’s probably been five years since we acquired a first lathe that didn’t work how we wanted, and then we bought the second one and restored that. We’ve been actively cutting for about two years.”

Rawlings and Welch’s timeline indirectly explains why they decided to go it alone—a choice owing not so much to stubbornness but a perceived lack of options and autonomy. When the pair began exploring vinyl production nearly a decade ago, analog’s comeback had started but was not yet in full swing.

“We didn’t know the people who could do our vinyl at this level,” Welch says. “I’m not saying there aren’t people. There’s so much good will out there for us and there are people who would have helped, but we didn’t know them. We’re so independent that we’re isolated. It’s our greatest strength and maybe our greatest failing. So we’re just doing it the way we think is correct.”

To many vinyl enthusiasts, “correct” means 100% analog from the master tapes—just as Welch and Rawlings do. And they not only cut 100% analog directly from analog tape, but have always recorded to tape and entirely stayed in the analog domain, even for editing and mixing. The practice is exceptionally rare in modern recording.

“That’s the way we’ve always done it—razor blades and tape,” states Welch.

“You have to be clear on what you’re doing, and the risk is part of it, and part of my art making. When you’re cutting and editing on analog tapes, that destruction and risk— carefully evaluated risk—is part of the art. It toughens you up. If you’re afraid you’ll destroy what you already did, you can’t finish. With digital, you don’t have to get rid of anything. Digital makes people soft. Analog forces you to take heed of the process.”

As it stands, few, if any, record labels—boutique or major—are paying closer attention than Acony.

4.5

4.5