Marketplace

2018 Rhino Records PRESSING

- Catalog Number R1 566970 - 603497860661

- Release Year 2018

- Vinyl Mastering Engineer Chris Bellman

- Pressing Weight 180g

- # of Disks 5

- Box Set Yes

- Jacket Style Other

- 100% Analog Mastering Yes

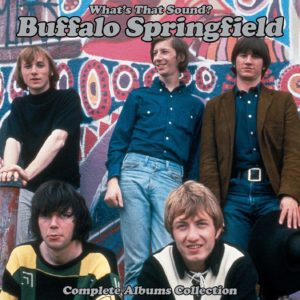

Buffalo Springfield came together in 1966, when pop music buzzed with possibility and change. The British Invasion had moved the emphasis on the charts from singers to bands and made it possible, even preferable, for musicians to write their own songs. American artists began to show the influence of their British counterparts, but Buffalo Springfield injected country and folk into its fare—and also used distorted guitars and other effects borrowed from the growing psychedelic-rock movement.

The group featured two formidable songwriters and guitarists in Stephen Stills and Neil Young, whose styles contrasted. Stills was smooth and professional, while Young was more eccentric and experimental. By Buffalo Springfield’s second album, rhythm guitarist Richie Furay started writing songs that underlined the collective’s country influences. Bad management and other factors contributed to the group’s brief lifespan, but its achievements on three albums—and the later successes of Stills, Young, and Furay—ensured Buffalo Springfield was pivotal to the development of 60s rock.

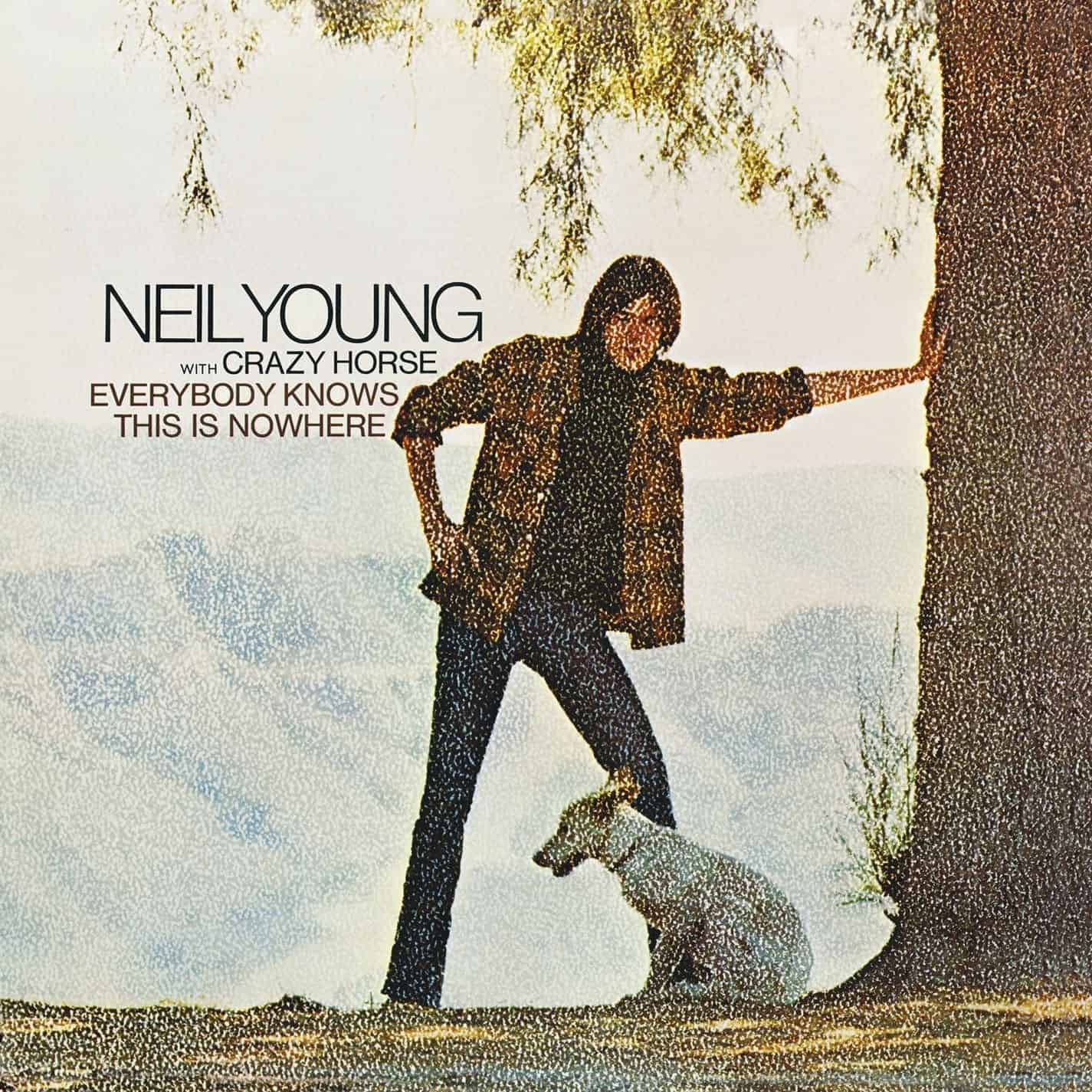

Rhino Records’ What’s That Sound? Complete Albums Collection gathers Buffalo Springfield’s three albums on vinyl in their originally released formats, more or less (more below). The five-LP set includes the first two efforts, Buffalo Springfield and Buffalo Springfield Again, in stereo and mono, and reproduces their covers in heavy cardboard with “tip-on” artwork. The quintet’s third effort, Last Time Around, was only released in stereo. The reissue’s cover reproduces the medium-weight cardboard packaging used on the original LP. Chris Bellman handled mastering duties, just as he did for many of Young’s reissues on vinyl.

Charles Greene and Brian Stone produced the group’s eponymous debut, and, as Young writes in the set’s liner notes, didn’t know any more about production than the musicians. ATCO released the work in late 1966 and made a second stereo pressing in March 1967 that changed the sequence of the songs, removing “Baby Don’t Scold Me” and moving “For What It’s Worth,” by then a hit, to the pole position on the LP.

Rhino uses the song lineup from the second pressing. On the reissue, harmonics on Stills’ guitar in the left channel on “For What It’s Worth” ring out with rounder tones and his voice is further out front and better defined. The acoustic guitar in the right channel possesses more clarity and harmonic depth, and the background vocals are more fleshed out. The remainder of the album benefits from the same level of transparency. While it sounds distant on the original LP, the country picking on “Go and Say Goodbye” snaps more brightly and steps out into the soundstage.

Guitars throughout sound deeper and more tonally accurate, and Dewey Martin’s drums feel more assertive. The full richness of the harmony vocals on “Do I Have to Come Right Out and Say It,” for example, make the album a much more rewarding listen than the earlier pressing, which sounds reserved by comparison. Bruce Palmer’s bass, nearly inaudible before, claims a much stronger presence, as does Martin’s bass drum, giving the music a firmer foundation.

“Burned,” Young’s song on side two, was originally recorded only in mono. On earlier stereo pressings, the track sounds like a failed attempt to process it into stereo—Young’s voice travels uncertainly to the right channel and the guitars and other instruments get vaguely placed in the center and left channels. The reissue wisely utilizes the mono recording.

The band was never happy with the album’s stereo release and supervised the mixing of the mono version. The LP of the latter edition in this box follows the original song sequence of the December 1966 release. In mono, the music gains more focus since it doesn’t use the extreme panning typical of many recordings of the time, including the stereo pressing of Buffalo Springfield. The guitars on “Go and Say Goodbye” occupy the extreme right and left channels in stereo, but in mono, they blend together in the center. Rhino’s mono version, like the stereo reissue, also brings the bass up, resulting in a fuller sound.

Guitar interplay and vocal harmonies gain from the improved focus in mono, and guitar solos, which sometimes seem to emanate from another room in stereo, better integrate with the rest of the music in mono. Here, they also have more texture. Fuzz guitars boast more roar and bite in both stereo and mono on Rhino’s pressings, but in mono, their solidity on “Sit Down I Think I Love You” and “Leave” makes them even more powerful.

Buffalo Springfield Again remains the work of several producers, including the musicians in the already fracturing band. Palmer had been deported to Canada for marijuana possession, and Young, already moving towards a solo career, popped in and out of the fray. Under the circumstances, the record feels remarkably cohesive. Furay wrote three songs and Young, who got only two lead vocals on the debut even though he penned five tunes, sings all the tracks he composed.

Marked sonic improvements distinguish Buffalo Springfield Again from its predecessor, even on the original pressing. The people behind the board had more experience and it shows. And the new pressing is more spacious than the original. While I initially missed the rocking overdrive quality “Mr. Soul” displays on the original, the vocals on Rhino’s reissue are more centered, Martin’s drums more three-dimensional, and the notes from Young’s guitar solos register clearly.

Acoustic guitars throughout resonate more openly, and lead vocals reflect a more immediate, realistic presence. Distorted guitars remain powerful and edgy, but there’s more space for other elements to come forward. Stills’ voice on “Everydays” is more clearly set off from the sustained, feedback guitar. Furay’s voice registers with greater nuance on “A Child’s Claim to Fame,” and the guitars and dobro are cleanly separated and easier to follow.

By extension, the guitar interplay on “Rock & Roll Woman” is easier to hear, and the harmony vocals are both deeper in the soundstage and nicely placed behind Stills. Young’s grand vision on “Broken Arrow” comes across with more force as the instruments enjoy better resolution. Acoustic guitars and piano lines that are difficult to hear on the earlier pressing have greater presence and enrich the song. Palmer’s bass (he sneaked back into the country to record), much better recorded on Buffalo Springfield Again than on the band’s debut, sounds more detailed and punchy throughout.

Buffalo Springfield Again is even better in mono. The guitars on “Mr. Soul” cut deeper and Young’s solos grab tighter. His voice comes out into the room even more firmly than it does on the new stereo pressing, and Palmer’s bass enjoys a more satisfying midrange attack. Harmony vocals on “A Child’s Claim to Fame” appear deeper in stereo, but the mono version presents them well. Furay’s lead vocal also has a bit more heft. The guitar and dobro don’t have a channel to themselves as they do in stereo, but amicably blend together, and the acoustic-guitar solos shimmer.

“Bluebird” sounds much more cohesive in mono, with Stills out in front of the band and the multitracked acoustic guitars creating a deep wall of sound. Bobby West’s bass strikes with added energy and Martin’s drums rock harder. The tune claims a striking rock n’ roll energy in mono, and the harmony vocals in the bridge are luxurious. Stills’ acoustic guitar solo hits with greater impact. “Broken Arrow” benefits from the expansive nature of stereo, but in mono, Martin’s kick drum pops and drives the song. Elements located in the background—even on the new stereo pressing—such as Jack Nitzsche’s piano, spring forward. Small details, including a vibraphone that adds color, are clearer in mono.

On the cover of the final Buffalo Springfield record, Last Time Around, Neil Young looks away from the rest of the band, as if ready to move on. In fact, the group had dissolved by the time the album got released. Jim Messina, who had been one of the engineers on Buffalo Springfield Again, produced and took over for Palmer on bass. A number of good songs pepper the album, which feels more like a collection of exploratory solo efforts than a finalized whole. Nonetheless, it hangs together and brings the band’s tenure to an honorable close.

“Kind Woman,” among the best Buffalo Springfield tunes, now unfolds with more magic. Pedal-steel notes hang in the air longer, guitar trills are firmer, the piano resonates with more authority, and Furay’s voice carries added conviction. The instrumental detail makes for a much more compelling experience.

Stills would later use parts of “Questions” for “Carry On” with Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. His voice sounds flat on the earlier pressing, and further obscured by flabby bass. Rhino’s version tightens the bass and other instruments, letting Stills’ voice register more clearly while also permitting the arrangement to flower. Young’s acoustic guitar strums on “I Am a Child” are now easier to hear, and his harmonica warmer and fuller. I felt as if I could reach out and touch the chimes ringing on Furay’s “Merry Go Round.” As with the other LPs in the set, careful mastering reveals more detail and makes the music more enjoyable.

All five of the LPs feature quiet surfaces, but each needed some cleaning to remove dust. Packaging is outstanding. You’ll be hard pressed to tell the difference between the artwork of the originals and the reissues, and the cover materials remain faithful to the originals. The overall box is comprised of heavy cardboard, and the photos capture the youthful energy of the band.

Chris Bellman’s mastering touts the same high quality he brings to many of Young’s analog reissues. Instrumental detail is greater than that of the original pressings—and never overemphasizes anything or changes the essential feel of the recordings. Because of the higher resolution, you’ll hear some occasions of brief sibilance in the vocals, but What’s That Sound? Complete Albums Collection delivers the best, most revealing versions of Buffalo Springfield’s music I’ve ever heard.

What’s That Sound? Complete Albums Collection

4.5

4.5