Given the selection between a monophonic (“mono”) and stereo recording of a rock or pop album from the 1960s, which would you choose? The 1960s witnessed the introduction of stereo playback in the home in a big way, opening up the opportunity for record companies to sell truckloads of new albums. Labels bet the farm consumers would go for “new and better” stereo recordings. They started recording pop music in stereo or mixing mono tapes to sound something like stereo—or sometimes, even electronically altering the recording to sound something like stereo.

A half century later, despite plenty of information suggesting mono can be as good or better than stereo reproduction, many buyers still gravitate to the latter when given the choice. It’s the safe option, after all. We all know stereo tops mono, right? Mono is prehistoric, the stuff your grandparents suffered through before stereo was invented. Well, as one old mono-era guy, George Gershwin, would say, it ain’t necessarily so! While every rock title available in both formats does not always prove superior in mono, a very high percentage of mono LPs slay their stereo counterparts.

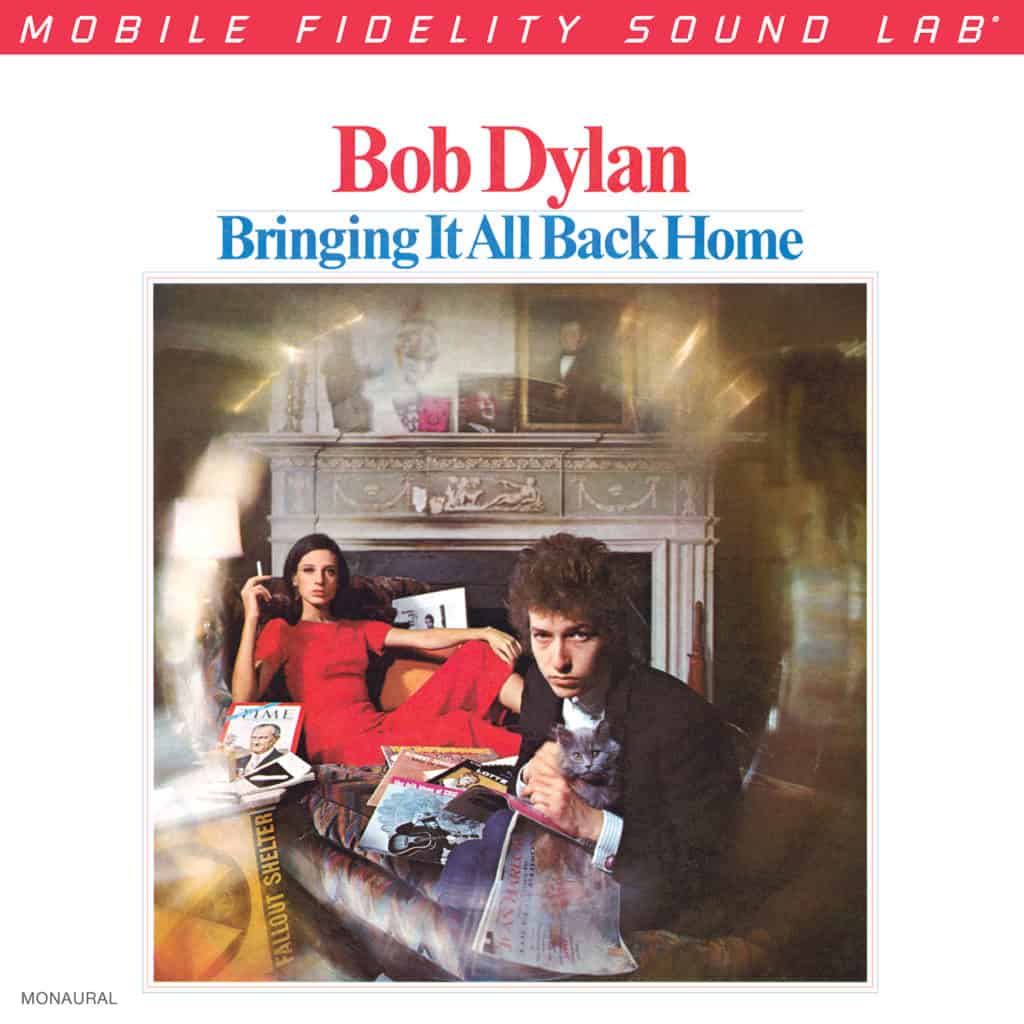

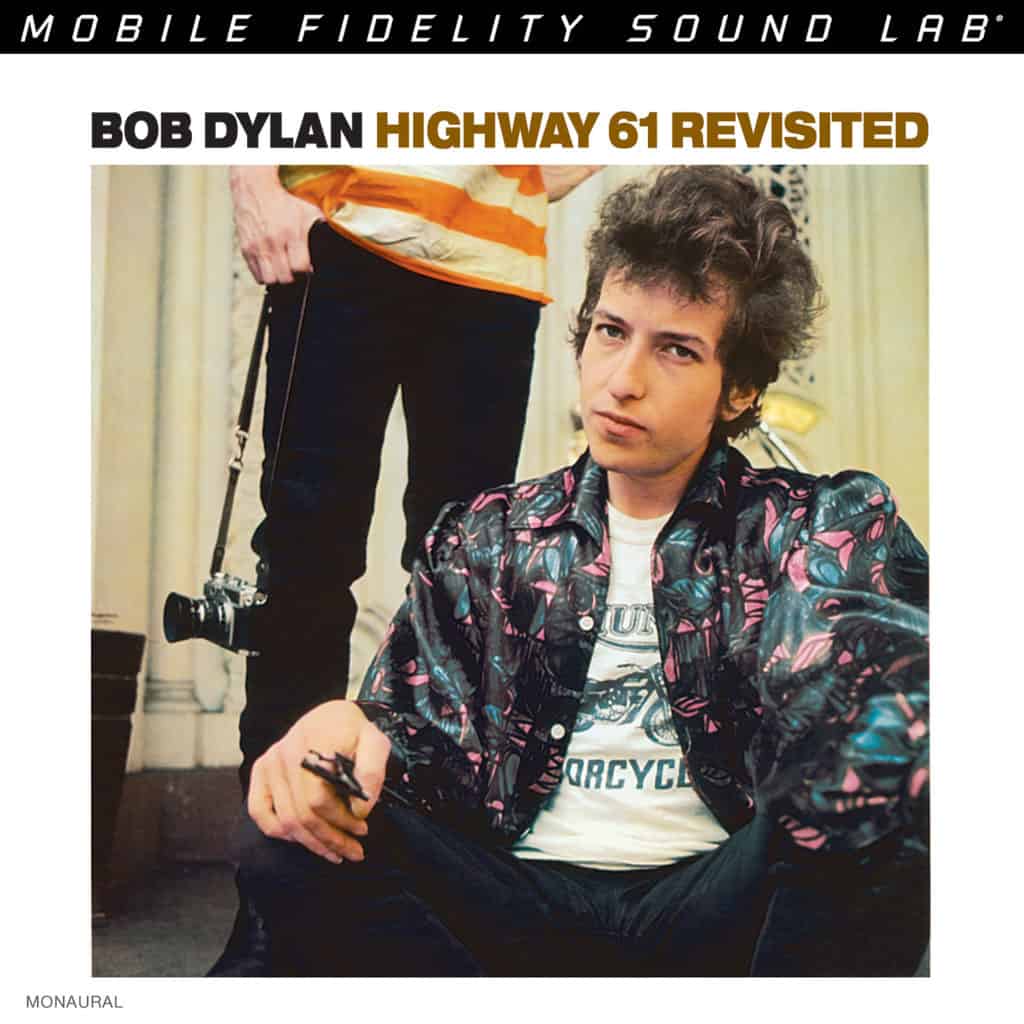

Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab’s (MoFi) recent release of seven of the first eight Bob Dylan titles on both stereo and mono LPs provides an exceptional opportunity for a mono-versus-stereo case study. Each MoFi Dylan reissue is produced as a numbered limited edition, and with one exception, comes as a 45RPM two-LP set housed in heavy cardboard fold-over covers. The exception? Blonde on Blonde, a three-record stereo box set that currently hasn’t a MoFi mono counterpart. Some of the audiophile imprint’s stereo titles have already sold out; others are available in limited quantities. All of the mono versions remain in print as of this writing.

Dylan released his debut, Bob Dylan, in 1962, and his eighth album, John Wesley Harding, in 1967, after the late 50s-through-mid-60s “golden age” of stereo classical music recording had passed. So why don’t stereo pop recordings from the same era share the same reputation for excellence as their classical brethren?

One reason owes to pop music’s slow adaptation of stereo sound due to the relationship between pop and AM radio. Unlike that of the classical market, AM radio drove sales of pop. If a pop record did not receive play on AM radio, few ever knew it existed. A low-quality signal, AM (amplitude modulation) was the earliest method for making radio transmissions and for decades stood as the sole method for instantly reaching a huge audience. It also remained limited to mono sound until almost 1970. Higher-quality FM (frequency modulation) radio claimed better quality but did not overtake the popularity of AM until the 1970s.

So if you wanted to make a hit record in the 1960s, you had to get it played on mono AM stations. And if you wanted to optimize the sound of your hit on AM radio, it had to be a mono recording, because stereo records played back in mono sound terrible.

It wasn’t just broadcasting that limited the enjoyment of stereo sound. Most homes until the late 1960s featured an entertainment system—called a hi-fi—built into a single cabinet. People were slow to respond to the seductive tactics of door-to-door salesmen pitching new stereo systems. Customers who did give into the stereo craze needed to be assured their old mono LPs would sound good on the new system. For example, early mono copies of Highway 61 Revisited proclaim the mono recording is “designed to play with the highest quality of reproduction on the phonograph of your choice, new or old. If you are the owner of a new stereophonic system, this record will play with even more brilliant true-to-life fidelity.” Stereo systems were fairly new in 1965, but sales hype is as old as the hills.

In addition to the limitations imposed by AM transmission and the lack of widespread acceptance of stereo playback in the home, a limited pool of recording engineers with experience recording in stereo further complicated matters. Somebody had to possess the technical know-how to record and master in stereo. Engineers called upon to start recording in stereo had, until then, spent their careers setting up microphones for mono recordings. Stereo recording required an entirely new microphone setup, and methods that worked for recording large orchestral works did not translate for small pop arrangements. Hence, engineers had to learn how a stereo recording should sound. The early solution resorted to panning different instruments into different spaces—some in the left speaker, some in the right speaker, and some in the middle. It didn’t take long to hear the deficiency of such an approach, but fixes did not appear overnight.

Even when dedicated mono and stereo tapes were rolling, the two didn’t receive the same loving post-production care.

The most famous examples can be heard on early albums from the Beatles and the Beach Boys, where the artists were very much involved in approving the mono mix and left stereo to other parties. Many such mono mixes greatly differ from the stereo mixes, with entirely different takes employed for the two versions.

Despite evidence to the contrary, record labels’ hype to sell stereo records created the impression mono was old-fashioned and inferior. The perception still persists. Don’t mono records sound flat, lacking the depth and width of a good stereo soundstage? Not necessarily. A well-done mono recording can fool many listeners into thinking they are experiencing stereo. Small-group mono recordings boast plenty of depth and stage width, and the instruments do not sound piled up together. In addition to such integration, first-rate mono records often feature better bass and dynamics than their stereo counterparts.

What prized mono records do not have is phony panned stereo sound, with two groups of instruments coming directly out of the two speakers and a voice floating in the middle.

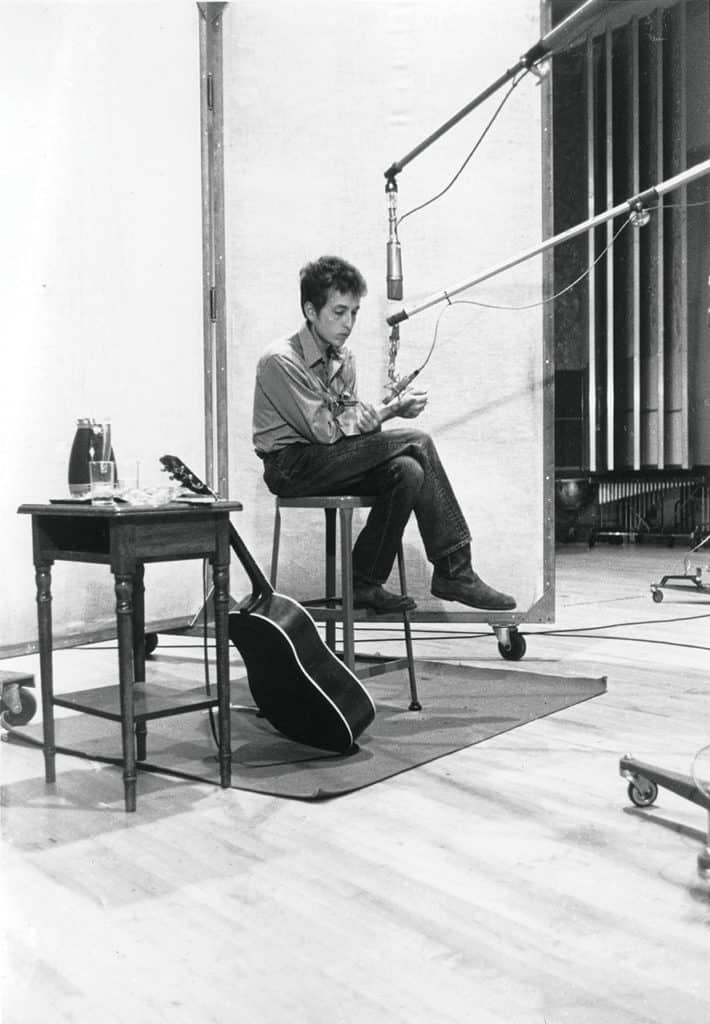

Dylan’s eponymous album—on which he plays solo on all but one song—ranks as one of the best examples of how different mono and stereo releases can sound. The 1962 recording sounds wonderful in its original mono version, but the recording engineers had a real problem with stereo. In the latter format, Dylan’s voice is right in the middle where it belongs, but his guitar gets firmly planted in one speaker and his harmonica in the other. In the early stages of stereo technology, records commonly potted instruments in the two speakers and the singer in the middle with little or no bleed to blend the sound. But it sounds just ridiculous for Dylan’s voice to be so far away from his guitar. No matter how good the recording and mastering, the stereo recording primarily serves as a demonstration of early stereo recording mistakes. MoFi’s mono version, sonically far superior to the original LP, is the way to go.

Dylan’s next three LPs are also solo acoustic albums. By then, the recording team adjusted its methods of recording stereo and abandoned hard panning. 1963’s The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan pulls the guitar much closer to the singer, yet the harmonica remains too far from his mouth. By 1964’s The Times They Are a-Changin’, engineers made another adjustment, bringing the instruments in tighter with the vocals. Later that same year, with Another Side of Bob Dylan, the last of Dylan’s four solo albums, the stereo version evidences even more tweaking, with the voice raised up a little high (compared to the mono version) and the guitar moved just a tad outside of where it should sit.

Taken together, Dylan’s four solo acoustic albums demonstrate there was no need or benefit from stereo tinkering. The mono versions showcase a feeling of integration between the voice and instrument tracks that the stereo versions cannot duplicate. Columbia’s engineers, all highly experienced with mono setups, prove you don’t need stereo recording to capture a solo performance.

MoFi’s mono versions of the four albums all improve on the sound of the mono originals, solidifying the realistic sensation of aural integration and dynamic impact.

Released in 1965, Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home changed all the rules. The singer no longer goes it alone and, even more shocking, one side of the album is electric. Dylan also veers away from the protest songs of his earlier work and aims straight for the surreal poetry that soon became his trademark. During early work on the album, Dylan met the Beatles, turned them on to weed, and sent them off to explore their more introspective side. Recorded at Columbia’s famed 30th Street Studios, Bringing It All Back Home displays not only Dylan’s leap into the future but a much more sophisticated approach by the Columbia team to record in stereo.

Musicians are spread out over a full soundstage and nothing sounds potted. Dynamics and tone color seem spot on, far exceeding what can be extracted from an original pressing. But there’s one problem with MoFi’s stereo reissue. It sold-out months ago, so good luck finding a copy. Because the original mono master tapes disappeared, MoFi’s mono edition is produced from the next-best source. And the mono demonstrates just how good the stereo version sounds. Of Dylan’s eight albums recorded in mono, Bringing It All Back Home stands as the only title where the stereo version proves more convincing—a fact that applies to both the originals and reissues.

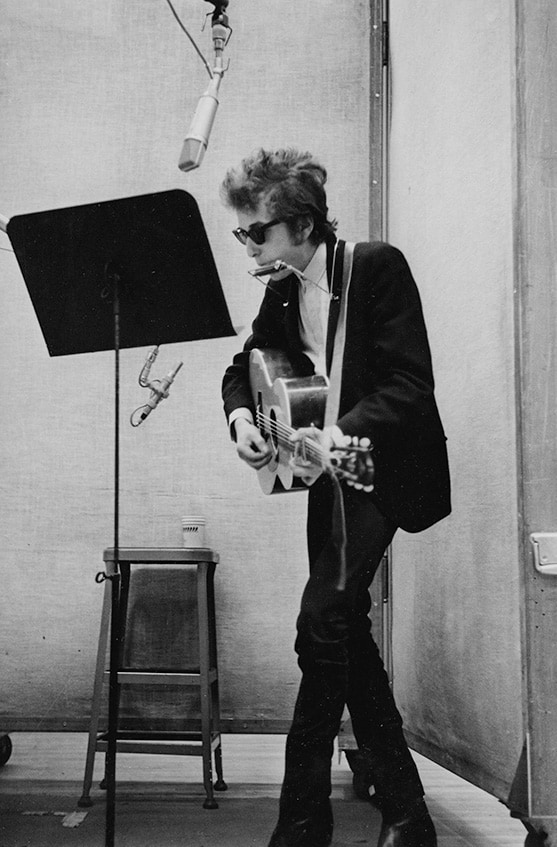

Dylan further amped up the electricity for his 1965 masterpiece Highway 61 Revisited on which his folk roots get left in the rearview mirror. MoFi worked from something other than the original masters for both the stereo and mono versions. Both reissues sound quite different from originals, but unlike the other MoFi Dylan reissues, Highway 61 Revisited does not sound significantly better than an early first pressing.

Unlike the other MoFi Dylan reissues, Highway 61 Revisited does not sound significantly better than an early first pressing.

Every time I listen, I can change my mind between mono and stereo versions—and between originals and the MoFi reissues. I find something to like in each. But it’s also important to take into account that buying a brand-new, beautifully made reissue on flat, quiet 180-gram vinyl from MoFi is a sure thing. Acquiring quiet originals in excellent condition on the used market can be time consuming, incredibly costly, and very frustrating when condition descriptions on expensive records skirt the truth.

Dylan’s subsequent release, Blonde On Blonde, takes the form of a double album in its original iteration. It gets spread across six vinyl sides on MoFi’s fabulous 45RPM stereo box set. MoFi has not indicated whether a mono version will appear in the future.

By 1967, most young people were listening to stereo systems and chose stereo over mono at the cash register. Stereo listening was fast becoming the norm. Sure, most folks didn’t set their speakers up properly, but they had two speakers firing somewhere in the room and weren’t turning back to mono any more than they were opting for black-and-white TVs. Record companies were happy they no longer needed to carry double inventory of titles.

Dylan’s 1967 album, John Wesley Harding, represents a huge departure from his work from just a few years earlier. It’s a pared-down acoustic Nashville production, with Dylan accompanied by only drums, bass, and steel guitar. (Dylan supplies guitar, harmonica, and piano.) Low-key music at the peak of the psychedelic era, it became the last Dylan album recorded in mono. MoFi’s stereo reissue throws a nice big stereo image, but pans the drum kit a bit afield. Compared to stereo, the mono MoFi throws almost as large a soundstage, but keeps the drums sounding like they are in the same room rather than abandoned in right field. The mono 2LP set also features greater dynamic snap and slightly more prominent bass. And the mono version is cut from the mono master, while the stereo is cut from a second-generation tape.

Mobile Fidelity boasts a multi-decade history of reissuing some of the greatest music available on vinyl in significantly improved-sounding versions. Its Dylan series, particularly the mono versions, stand alongside the label’s ongoing Miles Davis series as its two greatest achievements to date.

4.5

4.5