Marketplace

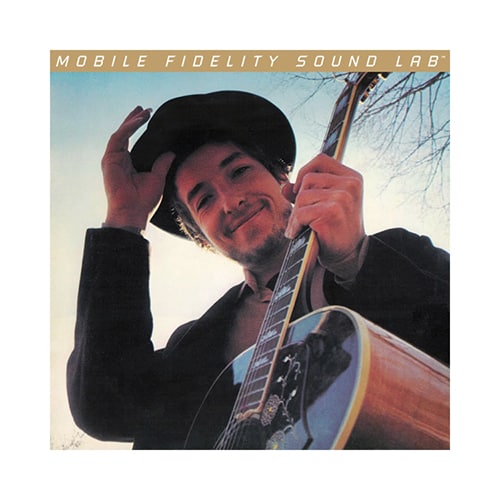

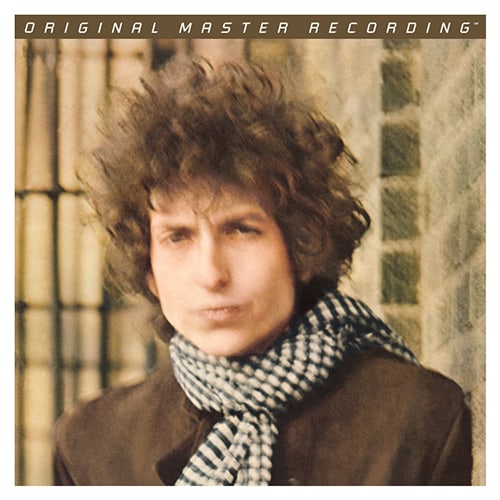

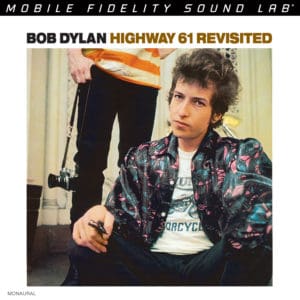

2016 Mobile-Fidelity Sound Lab PRESSING

- RPM 45

- Audio Mono

- Catalog Number MFSL 2-463

- Release Year 2016

- Vinyl Mastering Engineer Krieg Wunderlich and Shawn R. Britton

- Pressing Weight 180g

- # of Disks 2

- Jacket Style Gatefold

- 100% Analog Mastering Yes

- Pressing Plant RTI

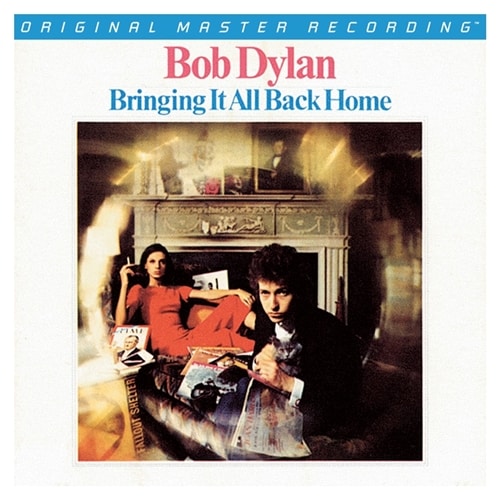

- Original Release Year 1965

- Original Label Columbia Records

- Original Catalog Number CL 2389

- Original Pressing Plant Columbia, Pitman

When listening to this album I think of this band or music:

When Bob Dylan exploded on the scene in the mid-1960s, few listeners were accustomed to his combination of songwriting prowess and profound swagger. But they only needed to look back a few short years to 1961 when Dylan’s label, Columbia Records, reissued Robert Johnson’s 1936 and 1937 recordings. Johnson witnessed virtually no commercial success during his short career. He is reputed to have sold his soul to the devil for the gift of musical genius. Given he died at the age of 27, he should have demanded longer life in the bargain. Like Johnson, Dylan masqueraded sophisticated musical style and hip poetry under the guise of a country rube. Few were fooled by either’s posture, but it added enigma to every verse they spun.

Music from this album would be a great soundtrack to this movie:

Bob Dylan’s filmography states his music has shown up in 756 soundtracks, and he has also appeared in movies playing a few forgettable roles as an actor. How do you capture Dylan’s essence in film without seeming overblown? You relax into your overblown nature with style. Dylan’s lyric “Now when all the bandits that you turn your other check to/All lay down their bandanas and complain/And you want somebody that you don’t have to speak to/Won’t you come see me, Queen Jane?” cries out for Joan Crawford’s Vienna and Sterling Hayden’s Johnny Guitar Logan—and their unique love story Johnny Guitar. Director Nicholas Ray was in many ways the Dylan of the directing world, and his classic movie remains his most Dylanesque creation, filled with inscrutable characters you just knew were even weirder in real life than on film. Hayden confirmed such an impression when he said, “There is not enough money in Hollywood to lure me into making another picture with Joan Crawford. And I like money.”

Few music lovers over the age of 40 have not heard Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited—or, at the minimum, they’ve at least heard songs from the album. Despite Dylan’s early reputation for slurred diction, I’d wager most listeners had no difficulty understanding all the lyrics of “Like a Rolling Stone” even if they didn’t grasp a word of it. Of course, many knew what it’s like to be on your own, to be invisible, to be scrounging your next meal. But how many got the heavy layer of blues references, that “rolling stone” derives from Muddy Waters’ song “Rollin Stone,” or that Highway 61 stands as a fundamental reference to the birth of the blues.

The road itself runs north and south, paralleling the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Minnesota. More notably, it courses through the Mississippi Delta country, the birthplace of the blues. Similarly, the route passes through Dylan’s birthplace in Duluth, Minnesota, making the bard’s connection with the blues a literal one. Highway 61’s intersection with the city of Clarksdale, Mississippi represents the “crossroads” immortalized in many songs in which blues legend Robert Johnson is said to have sold his soul to the devil. Ever since Dylan named his record after the highway, the area—and especially Clarksdale—became Mecca for blues fans as well as something of a tourist attraction. Even in 1965, however, most blues fans would have immediately understood Dylan’s allusion.

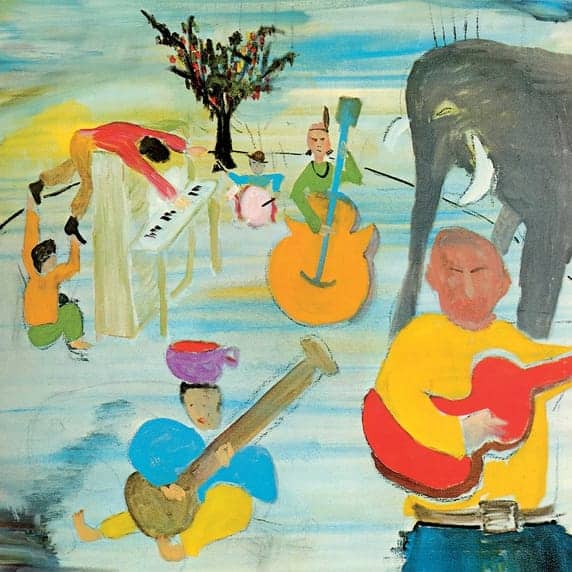

On the album, Dylan dusts off the acoustic folk roots of his past and fills his band with rock and blues players—including Michael Bloomfield on lead guitar. When the set came out in August 1965, it sounded like nothing else known to the public. The Rolling Stones were still in their period of recording derivative albums. And the Beatles had not yet released Rubber Soul. Indeed, the music was so unfamiliar that a month earlier, Dylan got booed at the Newport Folk Festival. The imagery and wordplay were equally fresh and stunning. No wonder almost every “greatest albums of all time” list includes Highway 61 Revisited somewhere in the top five.

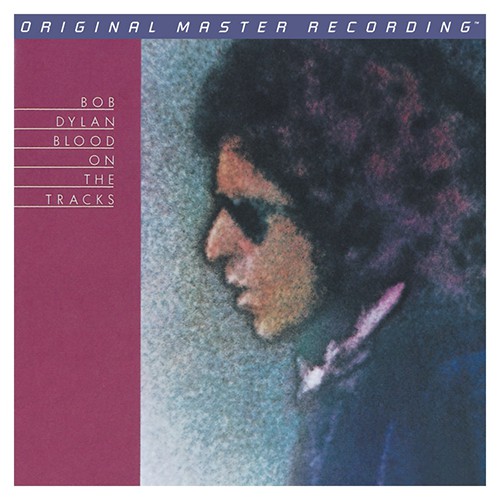

Recorded in the summer of 1965 at Columbia’s famed Studio A in New York, Highway 61 Revisited remains known for its big open sound. It was issued in both mono and stereo versions. Much speculation persists about the recording itself, with some experts claiming Dylan directly involved in preparing the mono mix and less involved with the stereo edition. The most collectable version of the album is the earliest stereo version. It features the wrong take of “From a Buick 6.” Someone—possibly Dylan—was paying more attention to the mono master.

Unlike their position in debates surrounding some mono versus stereo comparisons (such as The Beatles or Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band), mono advocates seem less fervent about Highway 61 Revisited. No significant difference exists between the mono and stereo mixes, so individual preference boils down to whether the album sounds better in mono or stereo. A dedicated mono mix, as opposed to a fold-down from a stereo recording, Highway 61 Revisited does not rank among the best recordings made in Studio A. Instruments are somewhat recessed (especially the bass drum and organ) and not especially well fleshed-out in space. The shortcomings appear on both the mono and stereo formats. Another factor leveling the playing field? The master tapes for both versions disappeared long ago. So, either way, any reissue will stem from something other than the original master.

Mobile Fidelity’s two-LP 45 RPM mono set presents a bigger, more robust image of Dylan than the original LP. The latter—and by that, I mean a very early pressing with the matrix series consisting of the number “1” followed by a single capital letter, e.g., “1A” or “1C”—projects an image with the instruments arrayed around Dylan on a wide, deep soundstage. Mobile Fidelity’s version grants slightly greater stage width but somewhat collapses the depth. The reissue also touts more bass weight and enjoys more dynamic punch. Consequently, it makes the original LP sound almost delicate.

In addition, the loss of the first-generation master tape results in the degradation of Studio A’s sense of nuanced acoustic. Late pressings of Highway 61 Revisited suffer from a similar deterioration, as if ennui set in at Columbia’s mastering facilities. And it isn’t just Highway 61 Revisited that displays the consequences. The year 1965 also marked the beginning of Miles Davis’ second great quartet recordings. Original pressings sound flat and lifeless, a symptom long uncorrected until Mobile Fidelity’s recent reissues. Between losing original masters or going flat in the mastering room, something was sliding down hill at Columbia or, as Dylan says in “Ballad of a Thin Man” on side two of Highway 61 Revisited: “Because something is happening here/But you don’t know what it is.”

Columbia/Sony proved more careful with the Miles Davis master tapes than the Dylan masters, so don’t expect the quantum leap in sound improvement experienced on Mobile Fidelity’s Davis reissues. Several of the audiophile label’s Dylan reissues, like Blonde on Blonde, significantly enhance the sonics heard on the original. With Highway 61 Revisited, if you have a very early pressing, you may prefer the original or, like me, be happy to hear two aspects Dylan—delicate and robust. Otherwise, the Mobile Fidelity version is a no-brainer because few of us can have (or afford) clean first issues. In short, Mobile Fidelity has taken one of the greatest albums ever committed to vinyl and given another generation a crack at hearing a masterpiece on flat, perfectly quiet vinyl in the best sound retrievable from the available tape sources.

Highway 61 Revisited (Mono)

4.5

4.5