Marketplace

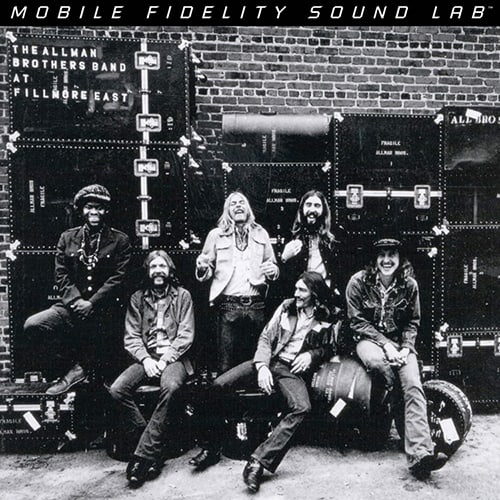

2013 Mobile-Fidelity Sound Lab PRESSING

- Catalog Number MFSL 2-398

- Release Year 2013

- Vinyl Mastering Engineer Krieg Wunderlich

- Pressing Weight 180g

- # of Disks 2

- Jacket Style Gatefold

- 100% Analog Mastering Yes

- Original Release Year 1972

- Original Label Capricorn Records

- Original Catalog Number 2CP 0102

When listening to this album I think of this band or music:

The Allman Brothers opened the doors for other Southern rock bands, so I think of the Marshall Tucker Band and Lynyrd Skynyrd when I hear Eat a Peach. I also think of Muddy Waters and Sonny Boy Williamson, both of whose songs are covered on the LP. And I recall Duane Allman’s sad, early death.

I would listen to this album while:

I’ve listened to this album while traveling, doing things around the house, and sitting to attentively listen. It can easily trigger lively conversations about the meaning of music in my life.

Music from this album would be a great soundtrack to this movie:

“Sweet Melissa” is a great romantic song and would do well in a love story. “Stand Back” could work in a film about a life gone bad. “Little Martha” could play in the closing moments of a film set in the deep, rural south.

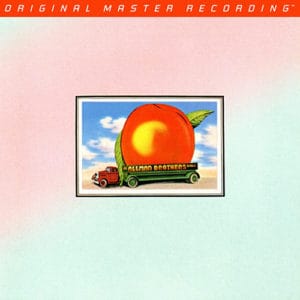

When Duane Allman died in October 1971, many harbored doubts about the Allman Brothers Band’s future. He served as the band’s leader and inspiration, and his loss dealt a devastating blow. The group finally had achieved success with At Fillmore East, released only three months before Duane’s death. But after a period of grieving, the collective decided to carry on.

The Allmans completed three songs for a new album before Duane died, and the surviving members recorded three more tracks when they returned to the studio a few months later. The resulting effort, Eat a Peach, includes those six songs as well as three live selections. One of the latter, the 35-minute “Mountain Jam,” serves as a continuation of At Fillmore East—you can hear its opening notes on that record’s fadeout. The other two live tracks here, “One Way Out” and “Trouble No More,” stem from a Fillmore show a few months later.

When I compare my Capricorn pressing of Eat a Peach, which I bought the day it was released, to the 2013-issued Mobile Fidelity version, the original is more forward and aggressive. The MoFi puts more space around instruments so that it’s easier to hear Jai Johanny Johanson’s congas on “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More.” Gregg Allman’s voice is also more clearly separated. Small bits of percussion in “Les Brers in A Minor” better emerge on the MoFi, as do Allman’s volume swells on the organ. The acoustic guitar on “Sweet Melissa” sounds warmer and more natural, and Dickie Betts’ guitar lines flow more easily with Allman’s voice. Cymbals feel crisper throughout. By contrast, Berry Oakley’s bass possesses more snap and energy on the Capricorn pressing and some guitar work, such as Betts’ slide solo on “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More,” has more force on the original, more aggressive mastering.

Also on the Capricorn, the studio recordings with Duane tout more air around the instruments, which lets you more effortlessly follow the two drummers, Johanson and Butch Trucks, on “Stand Back.” The acoustic and electric guitars on “Blue Sky” are better separated, and the acoustic guitars on “Little Martha” sound more natural. As with the other studio recordings on the album, solos come across as a little more reserved on the MoFi.

The live recordings on the album feature more open, spacious sonics on the MoFi, which gives Allman’s voice on “One Way Out” more clarity and lets each note on Betts’ solo fully resonate. The interaction of the band sounds clearer in “Mountain Jam,” where the accompaniment behind soloists is in greater relief and allows you to hear how well the band members responded to each other onstage. Once again, however, I find myself missing the way the Capricorn LP gives Oakley’s bass a more forceful sound—as well as a more palpable presentation of the Fillmore East’s atmosphere.

On balance, there are things to like about both pressings. I’ve played my Capricorn copy of Eat a Peach many times over the last 46 years—and far more than I’ve played the CD—as it powerfully conveys the liveliness and conviction of the music. The MoFi version lets you hear more of what’s going on, but occasionally loses some of the original pressing’s excitement and drive in order to clean up the sound. I like it the more I play it, but I will probably more often turn to the original.

Eat A Peach

4

4